Just a request for your patience as we figure out the future. And to thank you personally for the overwhelming love and support in the in-tray these last few days. I didn’t have the courage to read the avalanche of emails until yesterday, and I was blown away by your support for my decision to quit blogging and your overwhelming desire to see the Dish continue, if it can. So stay tuned. We’re figuring this out.

Author: Andrew Sullivan

Clearly A Cult

Logan Hill reviews Alex Gibney’s latest film, Going Clear, which got a standing ovation at Sundance last week:

Gibney (Taxi to the Dark Side, The Armstrong Lie) powerfully adapts many of the most devastating accusations from Pulitzer Prize winner Lawrence Wright’s book, Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief. First-hand sources, including Best Picture winner Paul Haggis, make emotional witnesses on the screen, dramatically offering their accounts of alleged physical abuse at the hands of Scientology leaders, including church head David Miscavige himself. The film draws a stark contrast between the group’s billion-dollar real-estate investments and the sub-minimum-wage pay most Scientology workers receive, which the film says averages about 40 cents per hour. There are awful stories of families torn apart and children separated from parents, a no-holds-barred critique of L. Ron Hubbard’s self-fictionalized biography (including allegations that Hubbard beat his wife, and comical mockery of the group’s belief in the “galactic overlord” Xenu).

Kate Erbland found the film “deeply unsettling”:

Miscavige comes across as an insane megalomaniac, but Gibney also fixes his gaze on a more meaningful target: Tom Cruise.

The brightest star in the Scientology constellation, Gibney and the ex-members don’t balk at making it clear that Cruise doesn’t just know about the organization’s transgressions, he also directly profits from them. Moreover, Gibney asserts that the church was directly responsible for the end of Cruise’s marriage to Nicole Kidman and that they additionally worked to turn the couple’s children against their mother.

Going Clear isn’t so much a call to action as a warning to Scientology that their methods and beliefs will no longer stand and that things are finally being done about it, people are no longer afraid to talk, and that the world will soon view them in a different manner — a shot, not a warning.

This shot came about a decade ago:

Update from a reader:

In addition to Matt and Trey’s efforts, the movie Bowfinger (1999) took a pretty good and not too veiled shot at the cult by depicting an organization called “Mind Head.” There are some hilarious sequences of the control they wield over their members.

Back to Gibney’s film, Sharan Shetty takes note of the financial angle:

Going Clear ends by noting that the church has fewer than 50,000 members but still possesses more than $3 billion in assets. Most of this wealth can be attributed to Scientology’s long, tortured, and ultimately triumphant battle with the IRS to be deemed a non-profit, tax-exempt organization. That victory is perhaps Miscavige’s keystone achievement: as the film details, and as the New York Times reported in 1997, Miscavige used a combination of lawsuits, backroom negotiations, and private investigators digging up dirt on IRS officials to secure Scientology’s status as a religion.

Scott Beggs gets the willies over the PR push against Going Clear:

[Aforementioned film critic Kate Erbland] hooked me by talking about how unsettling it is. Then, we got an email from a spokesperson for Scientology, that sealed the deal on my wanting to see the anti-Scientology movie. In the email, the representative:

- Implored us not to be a “mouthpiece for Alex Gibney’s propaganda”

- Chastised us for not first contacting the church for comment before posting a review of a movie

For the record, it’s not our policy to contact anyone before feeling double plus free to post our takes on movies we’ve seen (although Chris suggested we should get a statement from Ultron before reviewing Avengers 2). Also for the record, asking someone to post your official statement without vetting often goes better if you don’t open by accusing them of being propagandists by proxy.

And Katie Rife gives us a glimpse of the “social media smear campaign”:

One day after the film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, an account with the moniker Freedom Media Ethics, not quite as flashy as “Psychiatry: An Industry Of Death” but close enough, appeared on Twitter. The account, which as of this writing has 136 followers, links to a website credited to Church of Scientology International which contains a statement describing Gibney’s movie as “glorifying bitter, vengeful apostates expelled as long as three decades ago from the Church, [with a] one-sided result [that] is as dishonest as Gibney’s sources.” The website also compares the film to Rolling Stone’s UVA story and lists disparaging nicknames for each of Gibney’s sources in the film—The Soulless Sellout, The Hollywood Hypocrite, etc.

How Gibney has responded to such bullying tactics:

Great publicity. You can’t buy that, but they could, and we were the beneficiaries.

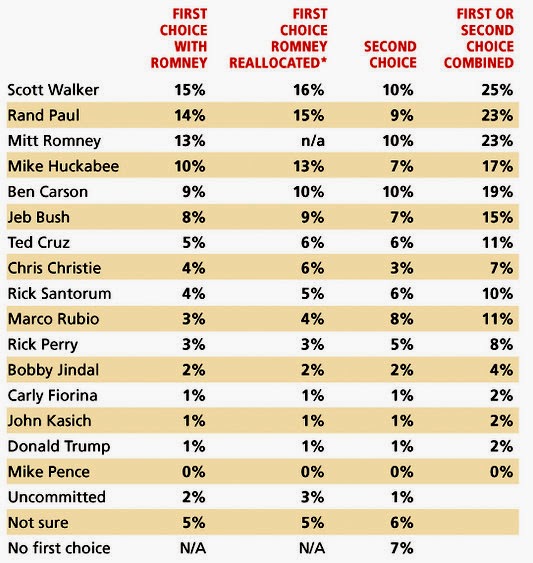

The Race Without Romney

Walker, Paul, and Huckabee sit atop a very early Iowa poll:

Andrew Prokop calls Romney’s exit “great news for Scott Walker.” But Tomasky is unimpressed by the Wisconsin governor:

I finally sat myself down and watched that Scott Walker speech from last week that everyone is raving about. If this was the standout speech, I sure made the right decision in not subjecting myself to the rest of them. It was little more than a series of red-meat appetizers and entrees: Wisconsin defunded Planned Parenthood, said no to Obamacare, passed some kind of law against “frivolous” lawsuits, and moved to crack down on voter “fraud””—all of that besides, of course, his big move, busting the public-employee unions. There wasn’t a single concrete idea about addressing any of the major problems the country faces. …

He’s gained [in Iowa] because those items— kicking Planned Parenthood, denying your own citizens subsidized health-care coverage, pretending that voter fraud is a thing—are what pass for ideas in today’s GOP. Walker is even more vacuous on foreign policy, as Martha Raddatz revealed yesterday, twisting him around like a pretzel with a couple of mildly tough questions on Syria. The Democratic Party has its problems, but at least Democrats are talking about middle-class wage stagnation, which is the country’s core economic quandary.

Matt Latimer expects Christie to benefit:

In fact, right after his tweak of Jeb, Mitt Romney headed to a dinner with the “fresh face” he apparently had in mind: the New Jersey governor. Many would-be Romney donors are reportedly following his lead. Should he enter the race, the Christie campaign strategy is not a mystery: To let everyone take whacks at Bush while Christie clings to the most valuable quality in all of presidential politics: being underestimated. The New Jersey governor shares many of Jeb Bush’s strengths: experience running a complicated, politically diverse state; an appeal to moderates; and with his proximity to New York, ready access to big-dollar donors. But he also has a few traits that seem to be notably absent from the third would-be President Bush: a crackling speaking style and a reputation for ruthlessness.

Jennifer Rubin downplays Christie’s chances:

Sources in the donor community say that large numbers of freed up former Romney donors, especially outside the Northeast, are steering away from the camp of New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie. (Christie took another hit when, not long after an earnest appeal in the Freedom Summit, he clocked in at 6 percent in the Des Moines Register/Bloomberg’s Iowa poll – with a 54 percent unfavorable rating.)

Paul Mirengoff looks at the big picture:

[T]he main effect of Romney’s non-entry may be to move the race more quickly to where it probably would have been after the early going — a field dominated by an “establishment” candidate (now probably Bush), a Tea Party favorite or two (probably Cruz and/or Paul), a “bridge candidate or two (say Walker and/or Rubio), and maybe Mike Huckabee if he retains his popularity among evangelicals.

Nate Cohn argues along the same lines:

There is one crucial respect in which the race has not changed. The main challenge to Mr. Bush will be from his right, from a candidate with appeal to the party’s conservative grass roots yet with enough appeal to the establishment to secure the resources necessary to win the nomination.

Mitt Romney was hoping to be that candidate. The position remains open.

Quote For The Day

“Democracies don’t need agreement. They do need tolerance of disagreement. The politically engaged — progressives and conservatives alike — mock the disenchanted majority for asking, “Why can’t we all just get along?” In one way, they’re right: Politics divides, and it should. In another way, they’re wrong. Getting along doesn’t require milquetoast moderation, flaccid centrism or “moving beyond left and right.” However, it does require some willingness to compromise, some curiosity about what might be valuable in the other side’s point of view, and some minimal attention to the civic virtues of tolerance and restraint,” – Clive Crook.

Busted With An Eggcorn, Ctd

The Dish thread that keeps on giving:

As a tyke in the 1940s, I often heard grownups talking about a very bad foreign man named – unless my ears deceived me – Hair Hitler. I had seen newsreel footage of this fidgety fellow with his unruly mop flopping about, so it never occurred to me to question why he was called “Hair.” When I grew a bit older and saw him referred to in print as “Herr Hitler,” I was in no way made wiser. “Herr,” I assumed, was how the Germans spelled “hair.”

Another reader:

We live in Texas and my husband is a diehard University of Texas grad, both undergrad and law school. So when our son was about three, he came into the living room during a UT football game. My husband flashed him the hook-em horns sign and told him what it meant. The kid started saying “honk em horns”. We laughed so hard and thought, well, it makes sense.

Another notes regarding our previous batch:

“Undertoad” is an eggcorn from John Irving’s The World According to Garp. I wonder if your reader traded it for their own memory or if they came to it on their own?

Full passage from Garp at the bottom of the post. Several more eggcorns from readers are below:

Though the eggcorn itself might not be suitable for Sunday Dish, I think the rest of the video is, since Father Greg Boyle of Homeboy Industries in LA talks about how we belong to each other, how we need to be tender with one another, how important community is. (I can’t tell you how much I value the Dish community and the work you all do!) The eggcorn is at 20:45. Fr. Greg is relating a story about one of his staff, a former gang member named Louis, who now frequently gives presentations about the work of Homeboy. Fr. Greg:

He was giving me tips on how to give a speech. He said, ‘You have to pepper your talk with self-defecating humor.’ I said, ‘Yeah, No shit.’

Heh. Another reader:

Not sure if this qualifies, but here’s my submission from only a couple of weeks ago. During a typical weekend winter squall, my in-laws had to cancel their visit out of concerns for safety on the roads. A few days later I mentioned to my nephew that I was sorry he wasn’t able to visit the previous weekend. His reply was that his father was afraid to go out because there was “a lot of black guys on the road.”

After puzzling over that for a few minutes, I asked him to repeat that in front of his father. Turns out my nephew overheard his father say there was “black ice” on the road. I only hope my nephew didn’t repeat that at school!

Another:

After my father’s funeral, my uncle told me that he had enjoyed the sermon, because the priest wasn’t “holier than now.”

Another:

When I was in grade school, Jewish friends would sometimes bring in gefilte (pronounced ga-fill-tah) fish during Passover. We had a fish tank at home, which I knew had a filter we changed from time to time. I thought they were saying “filter fish” and naturally assumed they were eating their tropical fish on matzo bread.

Lastly, here’s that passage from The World According to Garp:

Duncan began talking about Walt and the undertow – a famous family story. For as far back

as Duncan could remember, the Garps had gone every summer to Dog’s Head Harbor, New Hampshire, where the miles of beach in front of Jenny Fields’ estate were ravaged by a fearful undertow. When Walt was old enough to venture near the water, Duncan said to him – as Helen and Garp had, for years, said to Duncan – ‘Watch out for the undertow.’ Walt retreated, respectfully. And for three summers Walt was warned about the undertow. Duncan recalled all the phrases.

‘The undertow is bad today.’

‘The undertow is strong today.’

‘The undertow is wicked today.’ Wicked was a big word in New Hampshire – not just for the undertow.

And for years Walt reached out for it. From the first, when he asked what it could do to you, he had only been told that it could pull you out to sea. It could suck you under and drown you and drag you away.

It was Walt’s fourth summer at Dog’s Head Harbor, Duncan remembered, when Garp and Helen and Duncan observed Walt watching the sea. He stood ankle-deep in the foam from the surf and peered into the waves, without taking a step, for the longest time. The family went down to the water’s edge to have a word with him.

‘What are you doing, Walt?’ Helen asked.

‘What are you looking for, dummy?’ Duncan asked him.

‘I’m trying to see the Under Toad,’ Walt said.

‘The what?’ said Garp.

‘The Under Toad,’ Walt said. ‘I’m trying to see it. How big is it?

And Garp and Helen and Duncan held their breath; they realized that all these years Walt had been dreading a giant toad, lurking offshore, waiting to suck him under and drag him out to sea. The terrible Under Toad.

Garp tried to imagine it with him. Would it ever surface? Did it ever float? Or was it always down under, slimy and bloated and ever-watchful for ankles its coated tongue could snare? The vile Under Toad.

Between Helen and Garp, the Under Toad became their code phrase for anxiety. Long after the monster was clarified for Walt (‘Undertow, dummy, not Under Toad!’ Duncan had howled), Garp and Helen evoked the beast as a way of referring to their own sense of danger. When the traffic was heavy, when the road was icy – when depression had moved in overnight – they said to each other, ‘The Under Toad is strong today.’

‘Remember,’ Duncan asked on the plane, ‘how Walt asked if it was green or brown?’

Both Garp and Duncan laughed. But it was neither green nor brown, Garp thought. It was me. It was Helen. It was the color of bad weather. It was the size of an automobile.

Update from a reader:

Damn you, Andrew and Dish crew. You say you’re leaving, and then you copy Garp and I realize it’s been 15 years since I read that and I need to pull it out and read it again.

(Illustrations via Doug Salati)

Introducing “A Memorable Form Of Love”: An Interview With Spencer Reece

Dish literary editor Matthew Sitman writes:

This fall I had the pleasure of sitting down with the poet and priest Spencer Reece to record a long interview about his work teaching English, by way of poetry, to the girls who live at the Our Little Roses orphanage in San Pedro Sula, Honduras – a place also known as the murder capital of the world. You can read the entire interview in Deep Dish, which now is out from behind our paywall, and which includes my brief introduction to Spencer’s own poetry and the projects – a selection of the girls’ verse published in Poetry last month and a forthcoming documentary about Our Little Roses especially – that emerged from his time there. For those interested in Spencer’s background you can read a short biographical sketch about him here. The Dish featured his poetry last year here, here, and here. The interview itself tells the story of how Spencer found himself in Honduras and what he experienced there.

Below is an excerpt from “A Memorable Form of Love: An Interview with Spencer Reece,” in which he explains why it was while living in Honduras that he truly became a priest:

I don’t think I understood what it meant. I don’t think I understood what it meant to be a Christian. I don’t think I understood what the Eucharist meant. I don’t think I really understood any of it. I could repeat it intellectually, or write something on an exam. I had studied all of it. But it was all book knowledge, it wasn’t heart knowledge. I knew I was moving in the right direction, but I really didn’t know what it meant. But when I was with them, as time went on it, I began to understand all of it.

The Eucharist is a moment of intimacy, eating together, looking at each other. Like on the Road to Emmaus. And when I put the wafers in the mouths of all those girls lined up, I think I began to understand it.

Also, they have nobody, so they belong to God. There’s just no other way to explain it.

So then that began to make sense. I as a priest – as a shepherd, as a father, all those words that are used for priests – I literally became a father-like figure, which I’d never been, because I didn’t have children. I never thought I’d be in that position. That was happening to me. I believe what George Herbert wrote, that for him, he craved simplicity. And one of the things that he liked simple was his religion and his understanding of God, and that all God was, was love. As a priest, to communicate that message is what we’re supposed to try to do. We can’t do it perfectly, but that began to come through me. You know a priest really has to be there and not be there – the ego has to die in the spiritual life, so you have to kind of use yourself and not be there at the same time, so that God’s message can come through you. It’s not “Spencer’s” message. Of course it’s going to be some of my message, because it’s me, but you hope that there’ll be little sparks that are God’s that are coming through you. That seemed really important there with those girls.

Read the entire interview in Deep Dish – again, now without a paywall – here.

Intelligent Design 2.0? Ctd

Earlier this month we featured a number of critiques of Eric Metaxas’ assertion that recent developments in our scientific understanding of the universe points to the existence of God. Theoretical physicist Lawrence M. Krauss lays into Metaxas as well, asserting that his arguments about the improbability of any planet meeting all the criteria for supporting life makes the “familiar mistake of elaborating all the factors responsible for some specific event and calculating all the probabilities as if they were independent”:

In order for me to be writing this piece at this precise instant on this airplane, having done all the things I’ve done today, consider all the factors that had to be “just right”: I had to find myself in San Francisco, among all the cities in the world; the sequence of stoplights that my taxi had to traverse had to be just right, in order to get me to the airport when I did; the airport security screener had to experience a similar set of coincidences in order to be there when I needed her; same goes for the pilot. It would be easy for me to derive a set of probabilities that, when multiplied together, would produce a number so small that it would be statistically impossible for me to be here now writing.

This approach, of course, involves many fallacies. It is clear that many routes could have led to the same result. Similarly, when we consider the evolution of life on Earth, we have to ask what factors could have been different and still allowed for intelligent life. Consider a wild example, involving the asteroid that hit Earth sixty-five million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs and a host of other species, and probably allowing an evolutionary niche for mammals to begin to flourish. This was a bad thing for life in general, but a good thing for us. Had that not happened, however, maybe giant intelligent reptiles would be arguing about the existence of God today.

(Photo by Paul Williams)

Mental Health Break

Facing it all:

Burke Across The Pond

Reviewing Drew Maciag’s Edmund Burke in America, Bradley Baranowski details the complicated reception of the British statesman’s ideas on this side of the Atlantic:

While the goal is to say something about the national visions Americans have held, Maciag does illuminate much about how Burke’s ideas fared in the new world. Today most of us know Burke through his reaction to the French Revolution. That emphasis, however, is recent. Nineteenth century American Whigs such as Rufus Choate and Joseph Story downplayed the importance of Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), largely ignoring the text. Other figures such as the historian George Bancroft followed the same pattern. While Burke’s cautious attitude toward social change and his call for prudent reforms were palatable to many, even conservative Americans knew better than to defend views that could undercut their nation’s own revolutionary founding.

Maciag’s approach also reveals a tradition of thought that does not easily fit within the contemporary liberal/conservative dichotomy.

Many of his figures combine political reformism with cultural conservatism, package in an understanding of society’s laws as expressions of underlying traditions. He provides a series of concise, well-written close readings of key figures to explicate this theme. Maybe the greatest strength of this approach is that it both revitalizes interest in figures that we are familiar with and revives figures who have largely languished at the fringes of American intellectual history. Cultural conservatism’s relation to political progressivism (of various stripes) appears as crucial to understanding the thought of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. The Nation magazine, a crucial platform for cultural and political debate among Gilded Age liberals, was shot through with these Burkean themes during the final decades of the nineteenth century.

In all these examples, Burke functions not as a great preserver of tradition alone but as a crucial component in the “transition to modern America.” Burke’s whiggish views of history helped figures such as Roosevelt and Wilson reconcile their visions of America as an exceptional nation to the homogenizing forces of modernization. The relationship between progress and tradition was a balancing act rather than irreconcilable ideas. All it took was great leaders to keep the two in line.

Quote For The Day II

“For many folks, what’s most terrifying about death is the ending of their own being. Each of us is, naturally, at the center of a remarkably vivid life. We’re center stage in our own dramas of love and hardship, victory and defeat. The idea that it could just end, that we could just end, evokes nothing short of horror for many people. As Woody Allen famously put it: ‘Life is full of misery, loneliness and suffering — and it’s all over much too soon.’

This kind of existential terror never made a lot of sense to me. To explain why, I need you to know that when I was 9, my older brother was killed in an automobile accident. I saw him that afternoon, and he waved to me from across a field. Then I never saw him again. I was already an astronomically inclined kid, and that event, the most significant of my entire life, propelled me even deeper to questions about existence and time. Through all the grief and the questioning, one thought about death has always stayed with me:

I’m not concerned about the many years of my nonexistence before birth. Why then should I be concerned about the many years of my nonexistence that will follow death?

In other words, even though none of us existed 1,000 years ago, you don’t find many people worrying about their nonexistence during the Dark Ages. Our not-being in the past doesn’t worry us. So, why does our not-being in the future freak us out so much?

I am on record as being militantly agnostic about consciousness and death. I tend toward the ‘it’s all over when it’s over’ camp, but that, for me, is more of a hunch than a scientific position. Still, no matter how the universe is constructed with regard to death and its aftermath, empirically I think we can conclude that dread in any form is an unnecessary response. When it comes to our impending nonexistence, all we need do is let the past be our guide,” – Adam Frank, “What If Heaven Is Not For Real?”

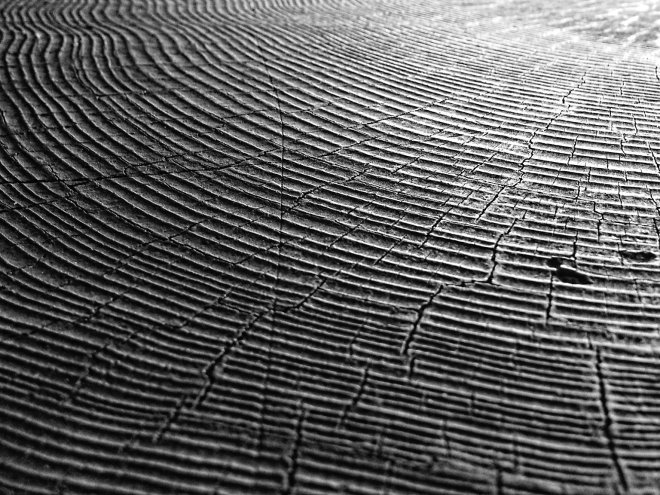

(Photo: Sequoia rings by Gabriel Rodríguez)