https://twitter.com/RaniaKhalek/statuses/553261940223778818

Update from a reader on the above image:

That cartoon looks bad, but if you understand the French, the meaning seems to me to be actually anti-racist. “La GPA” is “la gestation pour autrui,” or in English “surrogate motherhood.” The point of the cartoon is that when wealthy white couples pay poor women of color to be their surrogates, they are exploiting them. The point is somewhat bluntly and crudely made, but not at all offensive to my sensibilities. Others may differ, I suppose.

Jordan Weissmann urges us not to be afraid to criticize Charlie Hebdo‘s over-the-top (and often lame) humor even as we stand in solidarity with the victims of Wednesday’s terror attack:

So what should we do? We have to condemn obvious racism as loudly as we defend the right to engage in it. We have to point out when an “edgy” cartoon is just a crappy Islamophobic jab. We shouldn’t pretend that every magazine cover with a picture of Mohammed is a second coming of The Satanic Verses.

Making those distinctions isn’t going to placate the sorts of militants who are already apt to tote a machine gun into a magazine office. But it is a way to show good faith to the rest of a marginalized community, to show that free speech isn’t just about mocking their religion. It’s hard to talk about these things today, when so many families, a country, and a profession are rightfully in mourning. But it’s also necessary.

In Arthur Chu’s view, Charlie often violated satire’s unspoken rule to “punch up, not down”:

I mean, Muslims in France right now aren’t doing so great. The scars of the riots nine years ago are still fresh for many people, Muslims make up 60 to 70 percent of the prison population despite being less than 20 percent of the population overall, and France’s law against “religious symbols in public spaces” is specifically enforced to target Muslim women who choose to wear hijab—ironic considering we’re now touting Charlie Hebdo as a symbol of France’s staunch commitment to civil liberties.

Muslims in France are clearly worse off overall than, say, Jean Sarkozy (the son of former president Nicholas Sarkozy) and his wife Jessica Sebaoun-Darty, but Charlie Hebdo saw fit to apologize for an anti-Semitic caricature of Ms. Sebaoun-Darty and fire longtime cartoonist Siné over the incident while staunchly standing fast on their right to troll Muslims by showing Muhammad naked and bending over—which tells you something about the brand of satire they practice and, when push comes to shove, that they’d rather be aiming downward than upward.

The firing of Siné indeed showed a shameful double standard. Jonathan Laurence’s concern is that the chorus of “je suis Charlie” will play into the hands of the far right and normalize nastiness toward Muslims:

When the shock and sadness recede, it will become apparent that despite hashtags to the contrary, not all French “are Charlie Hebdo.” Numerous Catholic and Muslim groups offended by their cartoonists regularly filed lawsuits for incitement of racial or religious hatred against the newspaper—including after they republished the Danish prophet cartoons. Despite the understandable temptation to enter into a clear-cut opposition of “us versus them,” we can only hope that other political leaders will emerge to urge caution and respect while rejecting the murderers with every fiber of their being. It would be an unfortunate irony, and a distortion of these satirists’ legacy, if “politically incorrect” became the new politically correct.

Dreher asks whether Americans would be so quick to say “je suis” if the victims were from an organization we were more familiar with:

I can’t speak for French sensibilities, obviously, but here in America, it’s easy for us on both the Left and the Right to join the Je suis Charlie mob, because it costs us exactly nothing. Nobody here knows what Charlie Hebdo stands for; all we know is that its staff were the victims of Islamist mass murder, of the sort with which we are all familiar. We know that this murder strikes at one of the basic freedoms we take for granted: freedom of speech, and freedom of the press. Feelings of solidarity with those murdered souls are natural, and even laudable.

But what makes it kitschy is that we love thinking of ourselves standing in solidarity with the brave journalists against the Islamist killers. When the principle of standing up for free speech might cost us something far, far less than our lives, most of us would fold. You didn’t see liberals wearing “I Am Brendan Eich” slogans; many on the Left think he got what he deserved, because blasphemers like him don’t deserve a place in public life. Nor did you see conservatives brandishing “I Am Brendan Eich” slogans, because they feared they might be next.

Hear hear. Beutler, for his part, doesn’t think we need to praise Charlie in order to stand against terrorism:

The massacre in Paris has awakened a liberal tendency to valorize all objects of illiberal enmity. If an Islamist kills a westerner for a particular blasphemy, then the blasphemy itself must be embraced. We saw something similar just last month when countless Americans, rightly aggrieved by the extortion of a U.S.-based movie company, became determined to find reason to praise a satirical film they would’ve otherwise panned. This is clearly not always the correct reaction to terrorism or extortion. Here, liberals can learn a lesson from Second Amendment absolutists who nevertheless condemn open-carry demonstrations in fast food restaurants.

Likewise, Drum objects to the Dish’s framing of decisions by the WaPo and other news outlets not to republish Charlie’s cartoons as “capitulations”:

Anyone who wishes to publish offensive cartoons should be free to do so. Likewise, anyone who wants to reprint the Charlie Hebdo cartoons as a demonstration of solidarity is free to do so. I hardly need to belabor the fact that there are excellent arguments in favor of doing this as a way of showing that we won’t allow terrorists to intimidate us. But that works in the other direction too. If you normally wouldn’t publish cartoons like these because you consider them needlessly offensive, you shouldn’t be intimidated into doing so just because there’s been a terrorist attack. Maintaining your normal policies even in the face of a terrorist attack is not “capitulation.” It’s just the opposite.

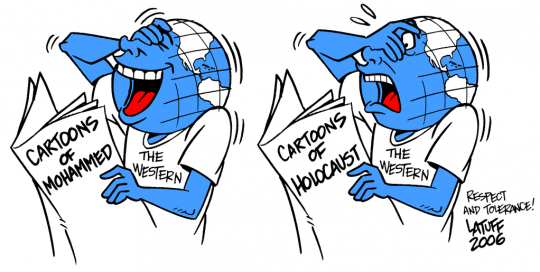

But the WaPo is a news organization, and these cartoons are at the heart of the news story of the Western world right now. News outlets can post the Charlie cartoons simply to show what all the fuss is about, without endorsing the images in the slightest. But as Dan Savage rightly asserts, they refuse to do so out of fear – the kind of fear that terrorists thrive on. The Dish, as it happens, has never posted anything from Charlie Hebdo outside the context of Islamists threatening or attacking them, mostly because their satire isn’t terribly good. Several years ago we posted a few cartoons from Carlos LaTuff before discovering that he’s a vile anti-Semite and that many of his cartoons reflect that (though not the two we posted), so we have since refused to feature any of his work. But if LaTuff became part of a news story like Charlie Hebdo has, we would certainly post his offending cartoons – like we did earlier this afternoon. Stephen Carter gets it right:

Many news organizations, in reporting on the Paris attacks, have made the decision not to show the cartoons that evidently motivated the attackers. This choice is sensibly prudent — who wants to wind up on a hit list? — but from the point of view of the terrorist, it furnishes evidence for the rationality of the action itself. Killing can be a useful weapon if it gets the killer more of what he wants. Terror seeks to raise the price of the policy to which terrorists object. In that sense it’s like a tax on a particular activity. In general, more taxes mean less of the activity. If you don’t want people to smoke, you make smoking more expensive. If you don’t want people to mock the Prophet Muhammad, you kill them for it. The logic is ugly and evil, but it’s still logic. …

The terrorist knows what scares us. He believes he also knows what will break us. Our short-run task is to prove rather than assert him wrong. In the long run, however, the only true means of deterrence is the creation of a new history, in which the terrorist is always tracked to his lair, and never gets what he wants.