Cillizza calls the outbreak in the US the “October surprise” of the midterms. How the epidemic fits into the pre-existing election narrative:

The country is as anxious and uncertain as it’s been in a very long time. Much of that anxiety had been laid at the feet of a deeply uncertain economic situation (the broad indicators improving without much to show for it closer to the ground) and the turbulence abroad (the Islamic State, Russia, the Middle East, etc.) coupled with a broader sense that the institutions that we once relied on (government, church, the justice system) are no longer reliable.

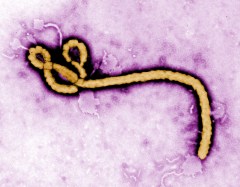

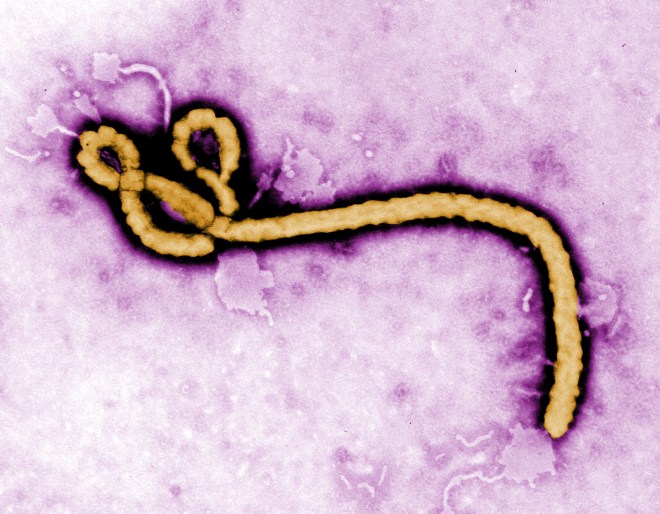

That sense of drift — caught between the old way of doing things and a not-yet-realized new way of doing things – is palpable in polling (huge majorities who say the country is headed in the wrong direction, a desire to get rid of everyone in Congress in one fell swoop) and in conversations I’ve had both with political professionals and average people. Ebola — with its sky-high mortality rate and lack of a vaccine – dovetails perfectly with those existing fears and anxieties.

Still, Waldman really wishes candidates would refrain from campaigning on it:

Here’s what I’d like to hear a candidate say when asked about this: “I don’t have an Ebola policy, because I’m running to be a legislator. It’s the job of legislators to do things like set budgets, but when there’s an actual outbreak of an infectious disease somewhere in the world, we should step back and let the people who actually know what they’re doing handle things. In this case, that’s the Centers for Disease Control. This is why we have a CDC in the first place, because if we were relying on politicians to keep us safe from infectious diseases, we’d really be screwed.”

You can call that an abdication of responsibility, but it isn’t. Even if Congress has an important role to play in setting policy priorities for agencies like the CDC, once there’s a potential crisis occuring, the idea that a bunch of yahoos like Pat Roberts should be determining the details of our response is absurd.

Nia-Malika Henderson observes that the public is weirdly confident in the government’s ability to handle an Ebola outbreak:

On the one hand, a new Washington Post/ABC News poll shows they are deeply dissatisfied with the effectiveness of the political system — a.k.a. all the people and processes that are in place to address things like health emergencies. The dissatisfaction is bipartisan, with 66 percent of Democrats and 80 percent of Republicans agreeing. But when it comes to Ebola, people are somehow confident that the federal government, which is (of course) part of that very same political system they deeply mistrust, has the ability to effectively respond to an outbreak. Again, that confidence is largely bipartisan, with 54 percent of Republicans and 76 percent of Democrats expressing confidence.

That’s still a significant gap, though. Looking at the same poll, Brendan Nyhan reflects on how partisanship drives the way people answer these questions:

This finding represents a striking reversal from the partisan divide found in a question about a potential avian influenza outbreak in 2006, when a Republican, George W. Bush, was president. An ABC/Post poll taken at the time found that 72 percent of Republicans were confident in an effective federal response compared with only 52 percent of Democrats. The partisan divide also appears to have grown as Republican disapproval of President Obama has deepened. …

These findings illustrate how people use simple partisan heuristics to make judgments about future government performance. Few people know about how the federal government responds to disease epidemics, but most people have views about President Obama and the job he is doing in office. That’s why Democrats are more confident in government’s capacity for an effective response than they were in 2006, for example, not because they approve of how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is being managed.