With cases in Texas and Spain raising alarms about potential Ebola outbreaks in the US and Europe, it’s worth remembering, as the above chart illustrates, how slowly the virus spreads relative to other contagious diseases, and therefore how unlikely a major outbreak is in a developed country with proper sanitation and extensive healthcare infrastructure. It’s also worth remembering that the situation in West Africa is, and will remain, far worse. In an interview with Julia Belluz, epidemiologist Lina Moses outlines why the number of Ebola cases there is probably underreported:

The cultural and socioeconomic setting have an impact on case counts. So do basic emotions. The chain of events for reporting cases has been interrupted by the fact that some Ebola victims go underground for fear of being taken away from their families. Imagine being the mother of a son who you think might have Ebola. You know your child might die, and you know that if you call authorities, he will most certainly die alone, far away from you, in an isolation ward where you can’t console him. Do you call that hot-line? “Communities are so afraid, so distrustful about what’s going on,” says Moses. “It’s hell. It’s devastating to the social fabric in communities, in towns and villages.”

This is compounded by denial about the disease. Though denial is less prevalent now, more than six months into the epidemic, for a period at the beginning — when Ebola emerged for the first time ever in West Africa — people just didn’t believe it was real.

Danny Vinik relays the scientific community’s worst fears:

[T]here’s a long-term concern, too, that Ebola will become endemic to West Africa—meaning it will be there forever with small outbreaks occurring frequently.

In September, the World Health Organization’s Ebola Response Team warned of such an outcome in the New England Journal of Medicine. “[W]e must therefore face the possibility that EVD (Ebola virus disease) will become endemic among the human population of West Africa, a prospect that has never previously been contemplated,” they wrote.

Many other health experts share their concerns. “That’s our biggest fear—that it will be endemic,” said Howard Markel, a medical historian at the University of Michigan. “That’s where you worry there will be little pockets of Ebola, whether in human beings or in bats or other animals, and that we’ll have little outbreaks or big outbreaks for years to come.”

Turning to the US, Laurie Garrett reiterates the need for a quick diagnostic test:

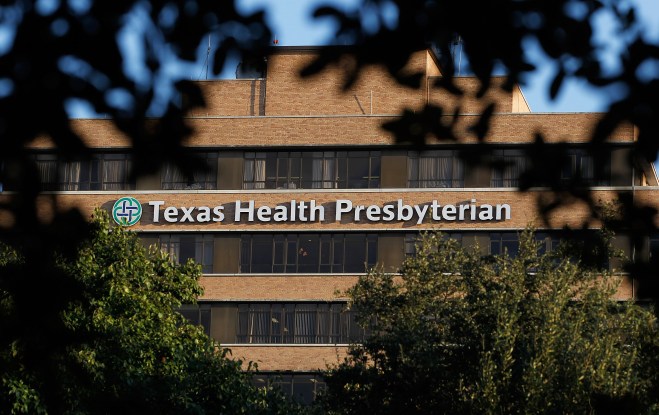

Such an assay would help quell the rising panic in the United States, prevent passage of laws that could be viewed as discriminatory against people of color and/or Africans, and provide nearly instantaneous hospital diagnosis. Rather than rattling the nerves of hundreds of Dallas parents afraid to return their children to classrooms visited by Duncan’s youngest contacts, public health officials could simply test the Duncan clan and assure the public that none are carrying Ebola.

Several tests are now in development, but the wheels of discovery, clinical testing, and federal approval require greasing. A point-of-care assay must be at the absolute top of the Ebola-control innovation agenda. Although compassion might dictate that the search for a treatment is of greater importance, the fact is that no tool — short of a 100 percent effective vaccine — can slow the spread of Ebola quite so dramatically. And though a vaccine may eventually emerge from the R&D process sometime in 2015, a rapid diagnostic could be in commercial production before Thanksgiving (with proper greasing of financial and regulatory wheels). Finger-prick tests for Ebola are in development now at Senova, a company in Weimar, Germany; at a small Colorado company called Corgenix; and at California-based Theranos.

And Jesse Singal touches on the challenges of fighting Ebola panic in the digital age:

Experts have actually known for a while that Ebola was going to show up in the U.S. Ever since the scope of the West African epidemic became clear, said [Columbia University epidemiologist Abdulrahman] El Sayed, American public-health officials have been hammering home the same message: “’There is gonna be an Ebola case here, but there’s probably not going to be a transmission.’” But before experts can effectively explain this, they first have to face down the biggest, scariest images of the disease lodged in the public’s imagination thanks to both fictionalized accounts and sensationalistic news coverage. “You have to address everybody’s worst fears before you can have a logical conversation about it,” said El-Sayed.

Update from a computational biologist:

That chart giving R0 values for various pathogens is kind of misleading, since it leaves off an important virus that most people are familiar with: influenza. R0 for influenza varies from around 1.0 to 2.4, i.e. right around the value for this Ebola outbreak. That doesn’t stop influenza from spreading everywhere pretty much every year and causing pandemics when novel strains appear. Ebola outbreaks can be brought under control because its transmission can be interrupted easily, not because its R0 is low.