Teju Cole shares a heartening report about Nigeria’s successful public health response to the Ebola crisis:

Meanwhile, Jon Cohen suggests that Ebola survivors could help stem the spread of the disease:

As far back as 431 B.C., the Athenian historian Thucydides recognized that people who survived the plague made for excellent caregivers. As Thucydides wrote: “It was with those who had recovered from the disease that the sick and the dying found most compassion. These knew what it was from experience, and had now no fear for themselves; for the same man was never attacked twice—never at least fatally.” Nicole Lurie, HHS’ assistant secretary for preparedness and response, is one of several doctors who suspect that people who survived Ebola may have developed immunity to that strain of the virus and could care for the infected with little risk to themselves. Lurie suggests that in these West African countries, where jobs are hard to find and Ebola carries such serious stigma with it that survivors sometimes are shunned, training survivors could be a win-win.

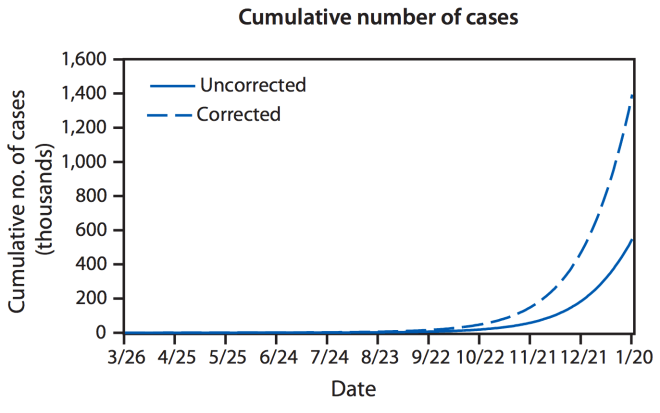

Michaeleen Doucleff notes that the CDC and WHO are on the same page when it comes to fighting the disease, but the horizon doesn’t look good:

Both agencies agree on how to turn the tide of this epidemic: Get 70 percent of sick people into isolation and treatment centers. Right now, [WHO’s Christopher] Dye says fewer than half the people who need treatment are getting it. If all goes well, Dye expects the goal of 70 percent could be reached in several weeks.

“Our great concern is this will be an epidemic that lasts for several years,” he says. The epidemic has hit such a size – and become so widespread geographically – that Ebola could become a permanent presence in West Africa. If that happens, there would be a constant threat that Ebola could spread to other parts of the world.

Rohit Chitale of the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center calls the international spread of Ebola “a significant possibility,” leaving poorer countries at highest risk:

The [CDC and WHO] and many nations have established guidance for entry and exit screening (e.g., thermal or fever screening at airports), and many nations had put them in place weeks or even months ago. Regardless, some cases will probably be imported into other nations. However, [if] cases occur in nations with a strong medical and public health infrastructure, like the U.S., patients that are suspected for Ebola will be isolated, exposed patients will be quarantined, and we would expect little to no spread of cases locally. So this is really not a direct threat for nations with robust health systems. But where resources are lacking and health systems are inadequate (as in West Africa), and where initial cases are not quickly discovered and managed, there is a real threat of local spread in the community from imported cases.

James Ciment argues that Americans have a special obligation to help those suffering in Liberia:

Pioneers from America settled Liberia and established it as Africa’s first republic; they modeled its institutions after our own. If we are true to our values and obligations, we will not abandon Liberia again once the current crisis has passed. Our government has earmarked an unprecedented sum to reverse the epidemic in Liberia and its neighbors. But as Americans, we can and should give as individuals. There are any number of organizations doing sterling work in fighting Ebola and aiding its victims—Doctors Without Borders, Save the Children, Global Health Ministries. Find one online and send it money now.