The World Health Organization (WHO) has upgraded the severity of the crisis:

The World Health Organization has declared the Ebola outbreak in West Africa a public health emergency of international concern on Friday. The organization is encouraging global coordination to prevent the spread of both the disease and of “fear and misinformation,” according to Keiji Fukuda, the organization’s Assistant Director-General. “This is an infectious disease that can be retained,” he said, noting the region’s poor conditions and need for help. “It’s not a mysterious disease.”

Susannah Locke asks, “So what does that actually mean?”:

Technically, it means that the WHO committee thinks the outbreak is a public health risk to other nations and that the outbreak might be in need of an international response. Those are the general criteria for the PHEIC category. This does not, however, mean WHO will go in and fix everything in the Ebola fight. The declaration itself comes with recommended things that various nations should do, but it doesn’t automatically come with funding, gloves, aid workers, or any of the other resources that the exceptionally poor nations with Ebola need to actually do those things.

Abby Haglage makes clear the scale of the problem:

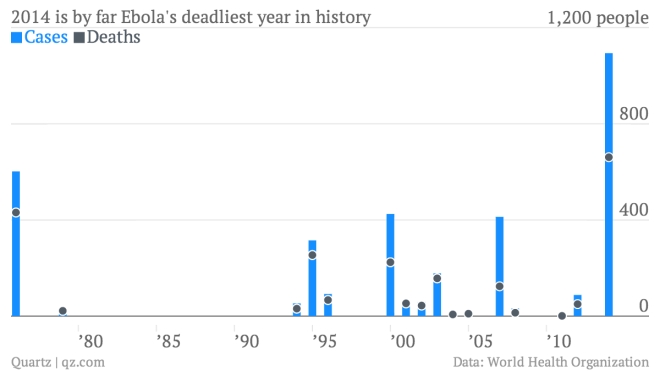

It’s already an unprecedented outbreak, CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden says, and the number of infected and killed by Ebola will likely soon outnumber all other Ebola outbreaks in the past 32 years combined. According to the CDC, there have already been more than 1,700 suspected and confirmed cases of Ebola in West Africa, and more than 900 deaths—numbers that Frieden later called “too foggy” to be definitive. Ken Isaacs, the vice president of Program and Government Relations for Samaritan’s Purse, painted an even bleaker picture. According to the World Health Organization, West Africa has counted 1,711 diagnoses and 932 deaths, already, which could represent only a small fraction of the true number. “We believe that these numbers represent just 25 to 50 percent of what is happening,” said Isaacs.

On a more cheerful note, Ronald Bailey predicts a future where such outbreaks have been all but eliminated:

Advances in fields like genomics, proteomics, reverse vaccinology, synthetic biotechnology, and bioinformatics are exponentially improving the knowledge of researchers about how pathogens and the human immune system interact. All of the tools involved with identifying pathogens and producing treatments like monoclonal antibodies and vaccines will continue to fall in price and become more ubiquitous. Thus will compounding therapies become ever faster and cheaper. Long, complicated, and expensive clinical trials overseen by hypercautious regulators will no longer be required for validating the safety and effectiveness of targeted, rationally designed therapies. A couple of decades hence, infectious diseases will still strike, but any patient with a fever will be tested, her infection immediately identified, and a personalized treatment regimen crafted just for her will be administered. We may reach a time when epidemics and pandemics are ancient history.