Late in the day on Friday, the White House announced that Loretta Lynch, a federal prosecutor from Brooklyn, would be Obama’s nominee to replace Eric Holder as his Attorney General. If confirmed, she would become the first black woman to hold the office:

Lynch is the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York, which covers Brooklyn along with Queens, Staten Island, and parts of Long Island. She has served twice in that post—initially during the end of the Clinton administration—and was confirmed unanimously by the Senate both times. But a promotion from federal prosecutor to leading the entire Justice Department would be a big bureaucratic leap, one that according to The New York Times has not occurred in nearly 200 years.

To Sam Kleiner, her outsider status is a feature, not a bug:

This independence is particularly important for the Attorney General because she may have to prosecute cases that are deeply unpopular. Lynch prosecuted both Republican and Democratic politicians on corruption charges and her lack of experience in the administration is actually a plus; she comes to the job with an integrity and independence that is owed to her rise through the ranks of a U.S. Attorney’s office. When President George W. Bush was sworn in 2001, Lynch had hoped to stay on as the U.S. attorney in the Eastern District because, she said, ”There’s a good group of people working here: the prosecutors, judges, agents and investigators.” For her, this was more than a job; ”It’s a like a family. I’ll miss the people most of all.” Bush asked for Lynch’s resignation but her willingness to serve under a Republican president demonstrates that she is not a political operative; she has sincerely dedicated her career to the Department of Justice.

Ilya Shapiro calls Lynch a smart, sensible choice:

Like George W. Bush’s appointment of Michael Mukasey to replace the embattled Alberto Gonzalez, Lynch is likely to be a low-profile steady hand to replace the radioactive Eric Holder. At the same time, picking the first black woman AG allows the president to further his diversity agenda without spending tremendous political capital (which he doesn’t now have) – in a way that wouldn’t have been possible with Tom Perez, the controversial labor secretary who was also thought to be a contender for the job. All in all, while I’m sure I’ll disagree with some of Lynch’s enforcement decisions, this nomination means that legal analysts’ focus will largely remain on those policy issues rather than the controversial personalities and politics behind them.

But Charles Ellison talks her up as anything but low-profile:

Obama’s future deployment of her skillsets should worry adversaries who will, predictably, dismiss the black woman in charge at Justice. Is Russian President Vladimir Putin still giving you geopolitical headaches? Obama now has a Lynch for that, her elevated role in Washington giving her extra firepower in her ongoing oil-trading and money-laundering investigation of Putin ally Gennady Timchenko.

Need to keep those multi-billion-dollar, post-recession big-bank fines flowing in to federal coffers? The Big Apple’s top prosecutor has been Holder’s secret weapon in squeezing historic penalties out of banks like Citigroup ($7 billion settlement) and HSBC ($1.2 billion) over seedy mortgages and money laundering. And Wall Street gets a bat signal over Gotham while Capitol Hill gets the notice letter: It’s Lynch who is patiently hunting down just-reelected Congressman Michael Grimm (R-NY), a former FBI agent indicted on 20 counts of tax fraud, perjury and obstruction of justice.

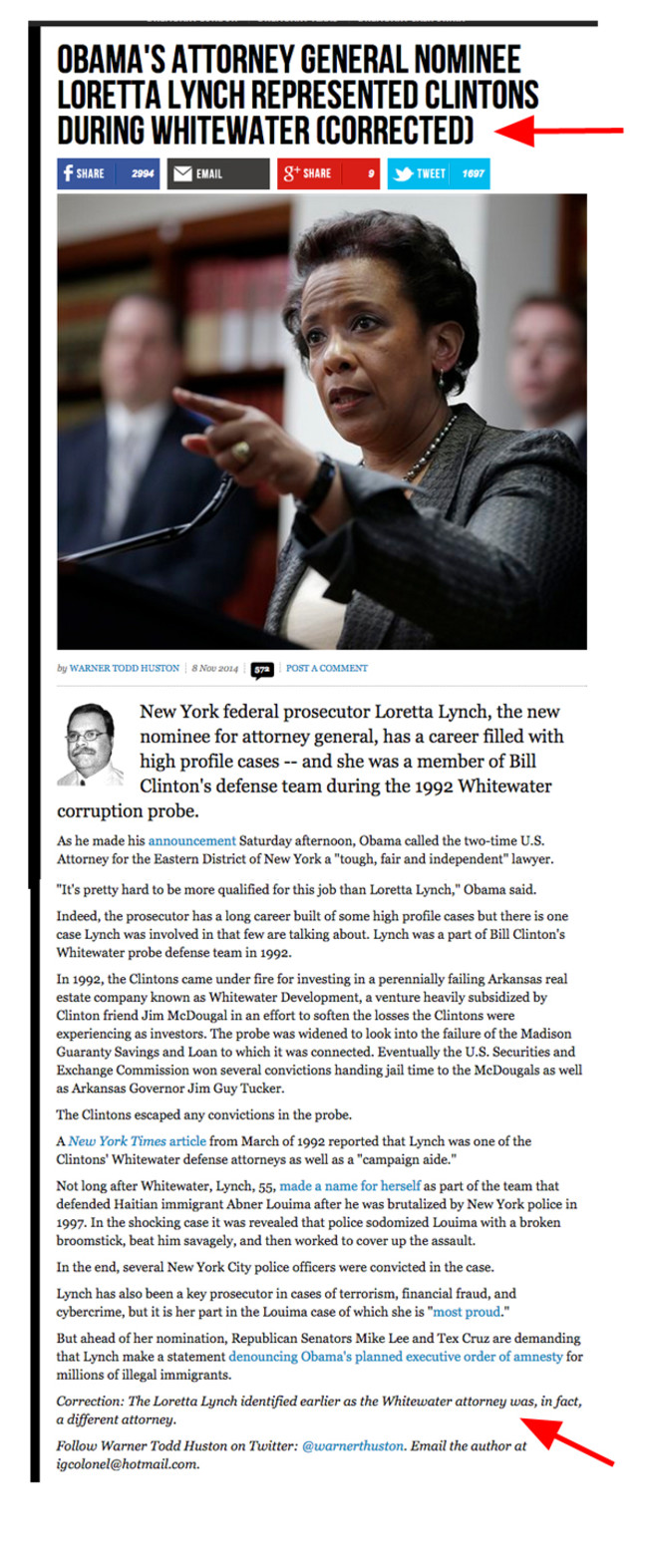

The administration hasn’t even set a date for her confirmation hearings, and already Lynch is making waves in the fever swamps, forcing Breitbart to issue what Josh Marshall calls “the best correction since forever”. Allahpundit wonders why Obama didn’t put forward her name before the election, to try and turn out more black voters:

Democrats were desperate to get black voters and women to turn out for them on Tuesday, so here’s Obama ready to nominate the first black woman Attorney General in U.S. history and … he saves the announcement for after the election. Even odder, Lynch is a North Carolina native; some free press about that a week or two before the big vote might have helped Kay Hagan in a tight race. Not sure why O held the nomination until now, unless the White House concluded that a black woman AG would only further antagonize an electorate that was sure to be older and whiter than 2012. If that was their calculation, though, it was stupid: Nearly anyone would be considered an upgrade over Holder by righties, especially someone like Lynch with few obvious red flags on her record. It could have helped with his base (a little) and wouldn’t have hurt with a wider electorate that was already prepared to bury Democrats.

Or maybe he’s just not that cynical. Senators Ted Cruz and Mike Lee insist that Obama wait until the new Senate is seated to start her confirmation process, which they plan to turn into a hearing on Obama’s threatened executive action on immigration reform. Lincoln Mitchell, however, posits that “a confrontational Senate seeking to stop Ms. Lynch might be more politically advantageous for the President”:

The challenge for the Republican Party now is to build on a very impressive election victory in the midterm election to help bring a Republican President to the White House in 2016. Central to this effort will be to recast the party as one that can govern rather than simply obstruct President Obama. The specter of a tough confirmation battle over a cabinet position will force the Republicans into demonstrating that they are capable of the former.

Republican opposition to Ms. Lynch may or may not be based on genuine policy concerns, but given that she has already been confirmed twice by the Senate it will be very easy for the White House to portray opposition to Ms. Lynch as typical Republican recalcitrance and as evidence that the GOP is still not ready to govern in a meaningful way. Additionally, because Ms. Lynch is an African American woman, any attempt to deny her confirmation will inevitably be seen through the prism of race and gender.