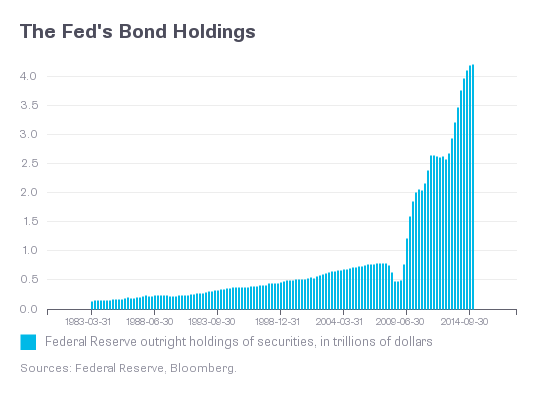

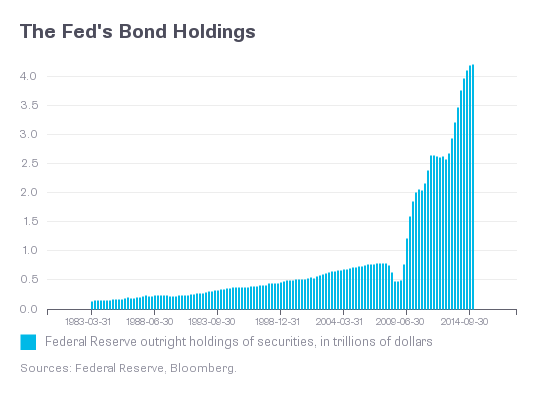

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve announced that it was halting the bond-buying program known as “quantitative easing”, the third round of which had begun in September 2012. While the Fed won’t divest itself of the more than $4 trillion in bonds it has accumulated, and has no immediate plans to raise interest rates, it won’t buy any more. Matt O’Brien fears that the Fed is sending the wrong signals as the economy remains lethargic:

The fact that it’s ending QE3 despite still-low inflation and still-high, though declining, unemployment, signals that the Fed is eager to return to normalcy. So does changing its statement from saying there’s a “significant underutilization of labor resources” to it “gradually diminishing.” The Fed, in short, looks much more hawkish. And that’s not good, because, as Chicago Fed President Charles Evans explains, the “biggest risk” to the economy right now is that the Fed raises rates too soon.

QE isn’t magic — far from it — but it is, as Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren told me, “quite effective.” Especially at convincing markets that the Fed won’t raise rates for awhile, which is all it should be saying right now. Because the only thing worse than having to do QE is having to do QE again. The Fed, in other words, should do everything it can to make sure the economy lifts off from its zero interest rate trap before it pulls anything back. Otherwise, we might find ourselves back in the same place a few years from now.

Justin Wolfers stresses that this isn’t really “the end” of QE, since the assets the Fed holds will continue to have a stimulative effect:

Of course, the aspect of Wednesday’s Federal Reserve decision that has captured the most attention is its decision to stop purchasing further long-term securities. But don’t confuse this with a monetary tightening. It’s hanging on to the stock of securities it currently holds, and the Fed’s preferred “stock view” says that this is what matters for keeping longer-term interest rates low. By this view, the Fed’s decision to end its bond-buying program does not mark the end of its efforts to stimulate the economy. Rather, it is no longer going to keep shifting the monetary dial to yet another more stimulative notch at each meeting. The level of monetary accommodation will remain at a historical high, even if it is no longer expanding.

Over recent years, policy makers have also worked to lower long-term interest rates by shaping expectations about future monetary policy decisions, in a process known as forward guidance. Today’s statement continues this policy, repeating recent guidance that the Fed expects interest rates to remain low for “a considerable time.”

But Ylan Mui suggests that higher rates may not be as far off as promised:

The debate over when to raise rates, which has already begun, will prove tricky for the Fed — and likely the biggest challenge of Janet Yellen’s tenure since she took over as head of the central bank early this year. Fed officials, who have suggested that the move could come in the middle of next year, hope that it causes little disruption. But achieving that delicate balance is the most basic dilemma of central banking. If the Fed moves too soon, it could undermine the recovery. If it waits too long, it could breed the next financial bubble as investors take too many risks backed by the belief the Fed will always be stimulating the economy.

When Fed officials suggested in the past that they may withdraw stimulus from the economy faster than anticipated, markets have swooned and interest rates have popped up. That’s one reason central bank officials have been preaching patience in responding to the strengthening recovery — but some investors believe they will not be able to wait much longer.

The Bloomberg View editors revisit the debate over whether QE worked. They maintain that it was the right call:

Exactly how much QE has helped the economy remains a matter of debate. Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said in 2012 that the Fed’s first two rounds may have boosted output by 3 percent and added more than 2 million jobs. In a more recent paper, San Francisco Fed President John Williams said such estimates were uncertain; he also noted the risks to the financial system posed by so large an intervention. Some believe QE has gradually diminishing effects; others that it has no positive effect at all.

Regardless, the gamble was justified. After the crash a persistent slump in demand hobbled the recovery and drove up long-term unemployment, threatening great and lasting economic damage. With inflation low, the risks of QE were small in relation to the possible gains. The benefits weren’t confined to the direct effects of the Fed’s purchases: Even more important, QE bolstered confidence that the central bank was willing to do everything in its power to revive the economy.

Danielle Kurtzleben also defends the program:

One key thing to consider with QE3 is the counterfactual — what would the economy have looked like had it never been put into place? One of the big benefits of QE3 was that it counteracted a Congress that insisted on holding back spending, even while the economy was sluggish. As Fed Chair, Bernanke was constantly chiding Congress for dragging on the economy, encouraging them to save deep spending cuts like those under sequestration for later.

So though 2013’s economic growth wasn’t exactly stellar compared to 2012’s, it’s important to consider how bad it could have been, says [economist Paul] Edelstein. “I mean, 2012 GDP growth was two and a quarter percent. 2013 comes, we have all the sequester-related spending cuts, and we have QE3. The result: GDP growth of two and a quarter percent,” he says. “Is two and a quarter percent good? Not really. But clearly again it could be a lot worse if we didn’t have fiscal drag.”