A wistful reader gets us started:

Priest Lake, Idaho. No good reason, except the photo reminds me of this place I love. It’s really heaven on earth. I wish I could be there now.

Another spins the globe:

Looking towards The Remarkables from Halfway Bay, New Zealand?

Another is thinking Canada:

I’m unfortunately short of time to do a thorough search. But I am living in the Okanagan area of British Columbia right now, and it sure looks like the territory around here, especially the dry bare hills. This is all assuming the U.S. flag is a red herring.

It isn’t. Another reader thinks he’s got it:

Finally something I know at a glance. It is the iconic mountain to all New Englanders, Mt. Washington. You can tell by the building at the summit. But where? Not north or south, and east is not likely since the view is blocked by Wildcat Mountain, so West we go and it seems to be at Forest Lake Rd. Where exactly? I don’t care, because it’s a beautiful day in the state of Maine and I’m going outside to enjoy that air.

Another gets us back where we belong, the American West:

I was pretty proud of myself for being correct that last week’s tree house view was in Costa Rica. This week, I may have to content myself with being correct that this lake house view is in the United States. OK, lake in the mountains. Probably not National Forest land, based on what look to be sparse settlements around the lake. The mountains are a little bit perplexing … they are shaped like Appalachians, but are relatively bare, like ranges further west. The vegetation looks more Western, too (though I am certainly no expert on this.) I can’t help but think that the key to this is the (apparent) structure on the mountain in the distance. An observatory, maybe? My best guess is the Meyer-Womble Observatory, near the peak of Mt. Evans in Colorado, but I cannot seem to find a big enough lake nearby to make sense of the view.

As Det. Bunk would say, this is a stone fucking whodunit.

Wendell Pierce, the actor who plays Detective Bunk in The Wire, was also in the movie Sleepers, which means he’s only one degree from this October-themed guess:

Any child of the ’70s and ’80s knows that spot. Camp Crystal Lake in Sussex County, New Jersey, home of the Friday the 13th films and a young Kevin Bacon’s demise.

A less murderous entry:

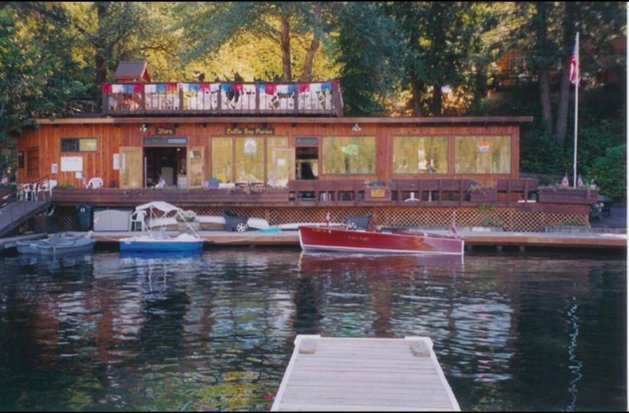

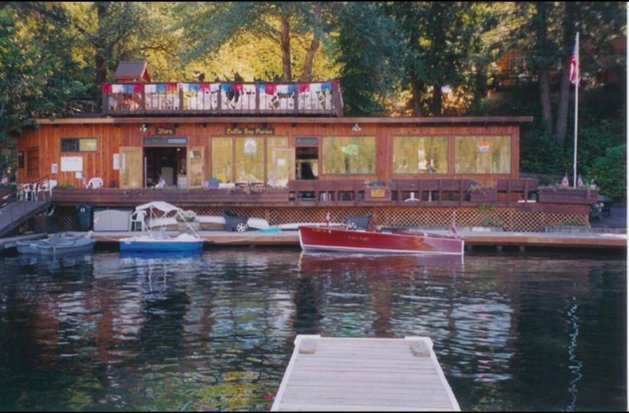

OK – this was a fun one. The trees looked northwestern. There was a snowy mountain, with a bump on the top that looked like a ski lift. Some scanning of Google maps revealed Schweitzer in Montana being near Lake Prend Oreile. This photo shows the top of Schweitzer and a comparable mountain range. Trying to triangulate the VFYW photo from there, it appeared Bottle Bay was the best location. And Bottle Bay Resort appears in a search for lodging:

My official guess: Cabin #6 at the Bottle Bay Resort, in Sagle, ID.

Another really struggled:

I know this isn’t right, but I had to throw something out into the VFYW Contest universe after nearly five hours of futile searching.

First of all, there is the American flag. Then I focused on whatever the hell that white thing is at the top of the distant mountain. Oh Dish Team, please tell me what that thing is. I looked at observatories, old hotels, power plants, radio towers, mansions – I couldn’t figure it out. There seems to be a stone arch bridge in the background (maybe). I googled those for a while to no avail. The only other clue was the pine tree to the left. Did I google types of pinecones to figure out what kind of tree it was? Absolutely. Is it a Sugar Pine? I think so. They mainly grow in California, Nevada and Oregon. The biggest body of water near those is Lake Tahoe. So I picked a city on that lake, and that was as close as I got.

I am eagerly awaiting the answer to this one. I’m hoping for lots of labels so I can learn what everything I couldn’t find actually is!

Our fave entry this week:

I thought “what if it’s not a lake, but a wide river?” So I traveled down the Columbia to the ocean. Lots of scenes that look similar, but nothing matched. Snake River. Klamath. Illinois. Nothing. Nothing. NOTHING!

Then there’s this object on the top of the mountain range in the distance:

What the fuck is that? Is it a building? A natural rock formation? A remote Mormon temple? None of the photos I looked at (and I looked at thousands) had anything like that. It sits there like a big middle finger, taunting me.

Lol. Another reader doubts the master:

I think even Chini won’t be able to pin this one done.

Not without some consternation:

You do this long enough and you start to break the views down into sub-groups. This week’s shot, for example, belongs to the “seemingly hopeless lake view” category, prior members of which include VFYWs #166, #114 and #125. These views tend to have few clues and no clear place to start searching. But once you get over the initial panic (for me this always involves running to Wyoming and looking desperately at Yellowstone Lake from every angle), the water views turn out to be surprisingly easy:

Another names that lake:

I’m just going to guess Lake Chelan, WA, because we got married on a dock on the lake and it was beautiful.

The town is Manson, Washington. Even when we try to stump even our most veteran players, we come away even more impressed with the caliber of play this contest inspires. A former winner takes us to school:

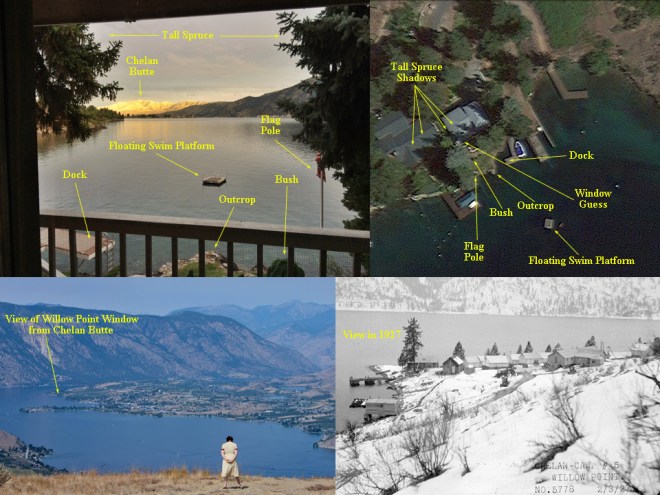

The search began by identifying the large trees by the cones visible in the contest photograph. Not much help, as the naturalized and cultivated Norway spruce is widely disturbed in many, mostly Northern states. I then looked for a large body of water with significant fluctuations in water level, which is apparent on the shoreline in the photograph and in the elevated docks with ladders. I assumed it was a lake created by a dam or one that fluctuated naturally. By chance, I began in Washington State in the area east of the Cascades but west of the drier parts of eastern Washington. Lake Chelan was a prominent candidate and fortunately a Google Earth photograph had a view with landmarks similar to that of the contest.

The rest was narrowing down the approximate location based on visible landmarks and searching for accommodations that might provide helpful images. The latter proved useless (at least for me). I eventually relied on Google Earth to identify the most plausible house along the most likely stretch of the lake’s northern shore.

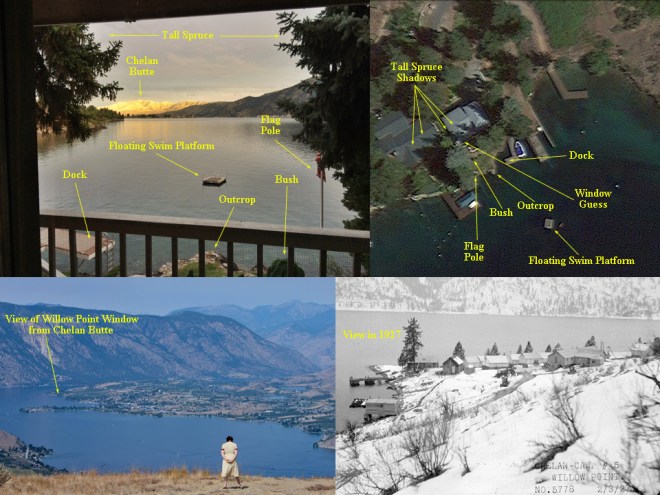

A big clue is that large stretches of the northern shoreline have been hardened or walled while that in front of the house and visible in the contest photograph had not. Finally I found a combination of features that resembled those in the contest photograph. These are illustrated in the attached (tall trees close to house, flag pole, bush in yard sloping to lake, prominent outcrop on shoreline, floating swim platform that is gray with white trim, and dock in the same location although apparently replaced recently). My window guess simply points to that part of the house which seems most probable. This is the only position that allows a view between the large trees while also capturing the flag pole, a portion of the dock, the neighboring shoreline, and distant landmarks. I assume the window is on the second floor.

The photograph is lovely.

Another former winner submits an equally impressive entry, and he was, aside from Chini, the only contestant to nail the exact address:

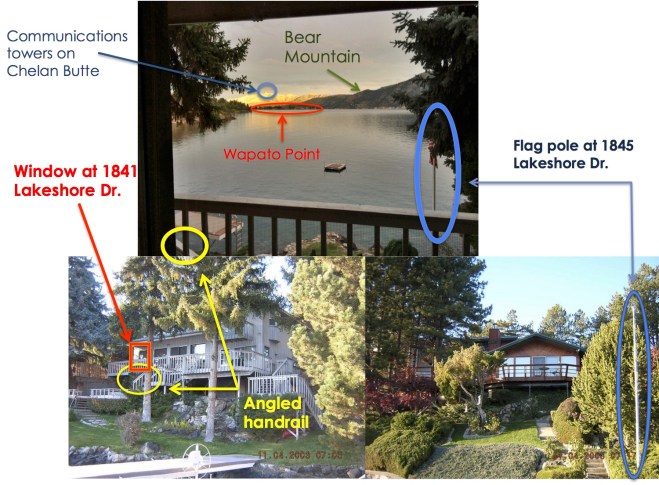

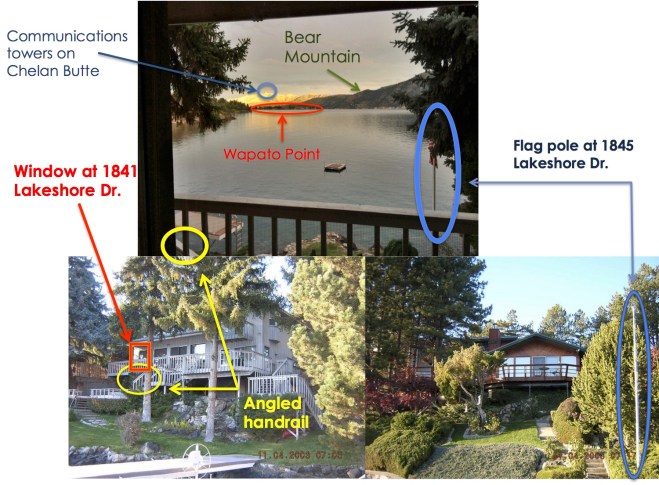

Back in Washington State this week. Instead of the shores of Puget Sound, we are on Willow Point looking out over Lake Chelan towards the Chelan Mountains. Specifically, we are admiring the view out of the back of 1841 Lakeshore Drive in Manson, WA 98831. Various online maps lacked an address for the home, but the county assessor’s office came through with a number. The window is the large window, furthest to the west on the main floor just above the porch. The attached picture identifies the window.

This week’s contest took time to solve. Obviously, the American flag ruled out Canada, New Zealand or South America. The combination of the lake, pine trees, and arid hillsides across the water focused the search on the boundary where the temperate forests of the west coast abruptly transition to the arid steppes of eastern California, Oregon and Washington. The Cascade and Sierra Nevada ranges cause the stark differences in rainfall between west and east. Unfortunately, I started in at the southern end of the line in the Sierra Nevada and worked my way north. And Lake Chelan is almost at the end of the line.

As for why I ended up on Lake Chelan, the combination of the numerous private docks and the communications towers on the mountain in the distance excluded many lakes and reservoirs along the way. Only Lake Chelan, it seemed, fit the bill.

The array of communications equipment on the far hill sits atop Chelan Butte. Also on the mountain live a herd of bighorn sheep. In 2004, the state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife released thirty-five bighorns to repopulate the area. Today, the state permits hunters to kill a handful of them each year (examples here and here).

Our resident neuroscientist calls this week’s view a “fairly tough one”:

The American Flag significantly constrains the search area, and the semi-arid landscape looks like various parts of the American West. The blue spruce on the photo’s right further indicates this. California can probably be excluded because draught conditions there make for much lower water levels that this lake. Similarly, the terrain is not quite as dramatic as the rockies, thereby excluding CO, it’s not as verdant as pacific NW locales like Coeur D’Alene area, and it’s not arid enough to be around Roosevelt lake near Yellowstone. Instead, the area looks a lot like the rain shadow of the Cascades, and indeed lake Chelan in WA turned up a hit based on landmarks in the photo.

Here is the heatmap of this week’s guesses:

This embed is invalid

And readers have been around there, of course:

I have two sets of fond memories of this area. My wife was waiting tables 40 miles uplake at Stehekin Lodge in North Cascades Park back in 1986 – till she crossed the owner’s son and got fired two weeks before the season’s end. I bailed on my job and joined her for some spectacular backpacking – even bad things sometimes work out right. Chelan is nice, but Stehekin and the North Cascades behind it are on a whole other level. As close to an Alaska-type remoteness as you’ll find in the Lower 48.

I also helped on a dam licensing project for Lake Chelan in the 2000s – trying to figure out how much water to release into Chelan Gorge for fish, whitewater boating, and aesthetics. It’s a tricky situation trying to keep the lake levels good for lake tourism, hydropower, flood control, and river values. The lake is natural, but has been raised about 20 feet. They drop it every spring so they can handle the runoff from the mountains and then try to keep it stable for the summer so all those people on the lake can use their boat docks. The “bathtub ring” in the photo is what gave the View away to me – I’ve spent a lot of time looking at rivers and reservoirs around the west, and knew we had to be on one of the few that are not incredibly low from the drought (most of those in California and the southwest), and had some pretty small lake level limits to work with. The spruce in the near view and the arid cascades basalt on the far side were the final tipoffs that we were in central WA.

Here’s a video of the whitewater boaters taking on Chelan Gorge just downstream from the lake. This is the flow releases provided for whitewater boating two weekends a year. Might make an interesting add-on mental health break:

Of the handful of players that guessed the right building this week, our winner had the most previous entries:

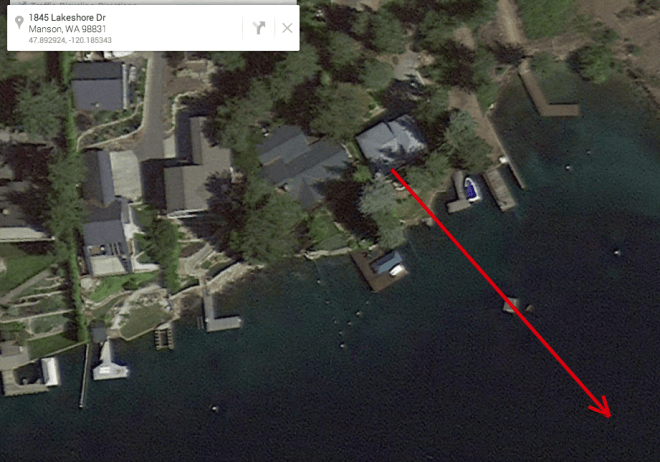

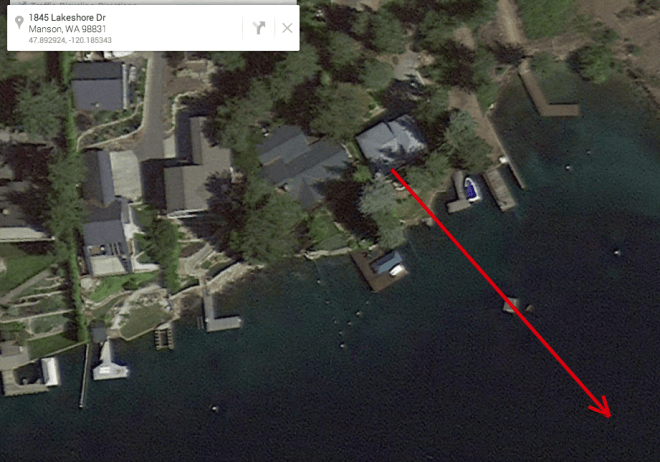

This is the SSW window of the guest house/annex at 1845 Lakeshore Dr Manson, Washington, looking southeast toward sunlit Chelan Butte, late afternoon. No doubt mine is one of literally thousands of correct answers. Savvy contestants will note the flag. OK, somewhere in the USA. I recognized Washington State right off the bat. The light vegetation on the sunlit highest peak suggests this view is somewhere along the north side of the south end of Ebola virus shaped Lake Chelan. That is Chelan Butte catching the last sun of the day and most of Lake Chelan is in shade at this time of day.

A close look at the photo shows what Google Maps IDs as Wapato Point jutting into the lake in between the window and Chelan Butte. So a bit of triangulation with Chelan Butte and the secondary peak to its west points us to the small bay at Lakeshore Dr and Willow Point Rd in Manson. The sunbathing platform is visible on Google, and its design and orientation match the photo. So this is the guest house/smaller unit at 1845 Lakeshore Dr. Which window? The one at the SSW corner, it’s the only window with a clear view to the platform given the large trees, and with the ladder of the “L” shaped dock visible in the lower left of the shot:

Missed it by one window, but still close enough for a win – congrats! This week’s view was actually submitted by last week’s winner, who also sends this entry-like explanation:

Winning last week and now my submission this week? #blessed.

It’s hard to look at this photo objectively because it’s a view that is so baked into my psyche. The view is looking southwest toward the foot of Lake Chelan (Shuh-LAN), the City of Chelan and Chelan Butte looming above it. In the middle distance, barely discernible, is Wapato Point, a peninsula-type feature that juts out into the lake. The white cut just above the lake on the right side is the state highway that runs along the South Shore of the lake. I’ll leave it to Chini to figure out the compass vectors. [Obliged: Southeast along a heading of 134.64 degrees.]

I’m conflicted about bragging too much about Lake Chelan because I don’t want to spoil what is, without a doubt, the jewel of Washington State. The stats themselves are pretty impressive: It’s the 3rd deepest lake in the country (after Crater and Tahoe) at almost 1,500 feet deep, a fact made more impressive in that it is a 1/2 mile across at its deepest point with 8,000 foot mountains that rising straight up from the shore. It’s 55 miles long. The head of the lake is in the North Cascades National Park and the location of a small town, Stehekin, that is only accessible by float plane, boat or foot. The City of Chelan, at the arid south end of the lake, sees a good amount of tourist activity (especially from Washingtonians from the wet side of the mountains looking for a respite from the rain and gloom). Lots of wine grapes and fruit are grown in the area. If you’ve ever eaten an apple, it was likely grown here.

The lake level is controlled by a dam near the City of Chelan. In the fall and winter months, the water goes down about 15 feet, leaving docks and boats high and dry. The glacial run-off from the surrounding peaks fill it back up for the summer. That’s why the ladder on the dock is out of the water. The black looking rocks on the left side of the picture show the high-water mark. The apparatus on the floating dock is simply to keep ducks and geese from resting there and shitting. They are prodigious shitters.

Chelan Butte is also a world-class paragliding venue. The photo below gives you an idea of the topography, although there is about a 800 foot differential between the Columbia River and the Lake Chelan valley. The star marks where the view photo was taken:

Another interesting fact: In November 1945, along the white cut on the other side of the lake, a school bus plunged into the lake during a snowstorm, killing 16 (15 kids and the driver, who had just returned from the war). Here’s a newsreel about the tragedy. There’s a roadside memorial that most people obliviously drive past on their way to taste local wine.

This aerial view gives a good perspective of Wapato Point:

The green orchards are either apples, cherries, peaches or grapes. Unfortunately, many of the orchards are being ripped out to put in housing developments. The village of Manson, home of the world famous Buddy’s Tavern, is tucked into the armpit of Wapato Point. The view is taken from the living room window. The street address is 1841 Lakeshore Drive, Manson Wa, although I’ll note that the Google address machine is not very good in rural locations. Any street address in the 1840s is acceptable.

Thanks again!

Thanks to you, and all our players. Come back Saturday at noon for next week’s contest.

Update from the reader behind our favorite entry, who is clearly relieved to have now identified the mountain-top middle finger:

There you are, you little fucker:

There’s actually a bit of history behind the Chelan Butte Fire Lookout. Built in 1938 by the Civilan Conservation Corps, it was manned until 1984 and provides a 360-degree view of the area, which includes Lake Chelan, the town of Chelan, the Wenatchee National Forest and the Columbia River. I did look at Lake Chelan, among several thousand other lakes, but never found a view that looked similar enough, and there just aren’t a lot of pictures of this structure from a distance.

Ah well … there’s always next week.

See you Saturday!

(Archive: Text|Gallery)

Thiel’s argument is broader: Not only religious vitality but the entirety of human innovation, he argues, depends on the belief that there are major secrets left to be uncovered, insights that existing institutions have failed to unlock (or perhaps forgotten), better ways of living that a small group might successfully embrace.