In an excerpt from his new book, The Glass Cage: Automation and Us, Nicholas Carr tackles the increasing automation of our society:

Machines are cold and mindless, and in their obedience to scripted routines we see an image of society’s darker possibilities. If machines bring something human to the alien cosmos, they also bring something alien to the human world. The mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell put it succinctly in a 1924 essay: “Machines are worshipped because they are beautiful and valued because they confer power; they are hated because they are hideous and loathed because they impose slavery.”

Machines are cold and mindless, and in their obedience to scripted routines we see an image of society’s darker possibilities. If machines bring something human to the alien cosmos, they also bring something alien to the human world. The mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell put it succinctly in a 1924 essay: “Machines are worshipped because they are beautiful and valued because they confer power; they are hated because they are hideous and loathed because they impose slavery.”

The tension reflected in Russell’s description of automated machines—they’d either destroy us or redeem us, liberate us or enslave us—has a long history. The same tension has run through popular reactions to factory machinery since the start of the Industrial Revolution more than two centuries ago. While many of our forebears celebrated the arrival of mechanized production, seeing it as a symbol of progress and a guarantor of prosperity, others worried that machines would steal their jobs and even their souls. Ever since, the story of technology has been one of rapid, often disorienting change. Thanks to the ingenuity of our inventors and entrepreneurs, hardly a decade has passed without the arrival of new, more elaborate, and more capable machinery. Yet our ambivalence toward these fabulous creations, creations of our own hands and minds, has remained a constant. It’s almost as if in looking at a machine we see, if only dimly, something about ourselves that we don’t quite trust.

In another excerpt, Carr fears that automation is damaging the labor market:

The science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once asked, “Can the synthesis of man and machine ever be stable, or will the purely organic component become such a hindrance that it has to be discarded?”

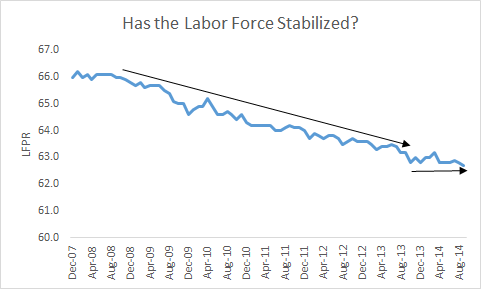

In the business world at least, no stability in the division of work between human and computer seems in the offing. The prevailing methods of computerized communication and coordination pretty much ensure that the role of people will go on shrinking. We’ve designed a system that discards us. If unemployment worsens in the years ahead, it may be more a result of our new, subterranean infrastructure of automation than of any particular installation of robots in factories or software applications in offices. The robots and applications are the visible flora of automation’s deep, extensive, and invasive root system.

Nick Romeo lays out some of the book’s primary arguments:

We are increasingly encaged, [Carr] argues, but the invisibility of our high-tech snares gives us the illusion of freedom. As evidence, he cites the case of Inuit hunters in northern Canada. Older generations could track caribou through the tundra with astonishing precision by noticing subtle changes in winds, snowdrift patterns, stars, and animal behavior. Once younger hunters began using snowmobiles and GPS units, their navigational prowess declined. They began trusting the GPS devices so completely that they ignored blatant dangers, speeding over cliffs or onto thin ice. And when a GPS unit broke or its batteries froze, young hunters who had not developed and practiced the wayfinding skills of their elders were uniquely vulnerable.

Carr includes other case studies: He describes doctors who become so reliant on decision-assistance software that they overlook subtle signals from patients or dismiss improbable but accurate diagnoses. He interviews architects whose drawing skills decay as they transition to digital platforms. And he recounts frightening instances when commercial airline pilots fail to perform simple corrections in emergencies because they are so used to trusting the autopilot system. Carr is quick to acknowledge that these technologies often do enhance and assist human skills. But he makes a compelling case that our relationship with them is not as positive as we might think.

But, after reading the book, Josh Dzieza remains unafraid of such technologies:

Carr takes a broad approach to automation, so any technological abbreviation of a task would qualify. Google’s auto-completing searches automates inquiry, Carr says, while legal software automates research, discovery, and even the drafting of contracts. CAD automates architectural sketching. Thanks to an explosion in computing power, more and more things are getting automated, and Carr worries that it’s all combining to degrade our skills and insulate us from the world. “When automation distances us from our work,” Carr writes, “when it gets between us and the world, it erases the artistry from our lives.”

I think Carr is probably right about much of this, but I have a hard time mustering his concern. I too am nostalgic for the romance of early flight, when pilots were intuitively attuned to their surroundings through the shuddering of their plane’s throttles and levers; but as Carr himself notes, a great many of those early pilots died in crashes, and personally I’m glad my captain isn’t flying by unaided gut feeling. Pilots might be less manually skilled now, but flying is far safer. For my part, I’m probably less engaged with my surroundings because of Google Maps, but it also allows me to explore more new places without getting lost. Every tool, automated or not, opens new possibilities and closes others, fosters new skills and lets others lapse. Most of the problems Carr points to either seem like good trade-offs or fixable shortcomings. He even suggests some possible design solutions, including taking cues from game makers and designing tools that are always slightly challenging to use.