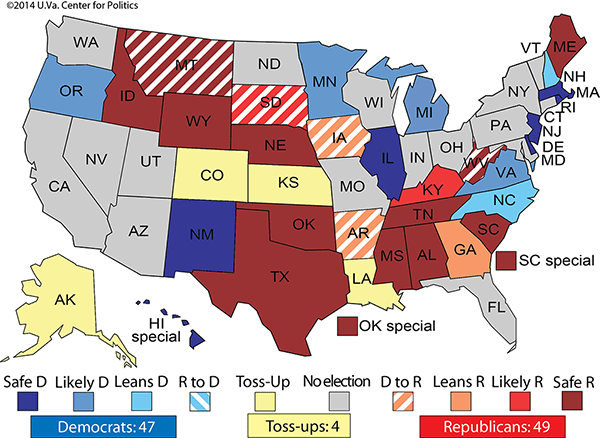

So many undecided contests are winnable for the GOP that the party would have to have a string of bad luck — combined with a truly exceptional Democratic get-out-the-vote program — to snatch defeat from the wide-open jaws of victory. Or Republicans would have to truly shoot themselves in the foot in at least one race, which has become a clear possibility over the last few weeks in Kansas.

Yesterday, Andrew Prokop flagged a Kansas poll:

Senate Democrats have gotten bad polling news in several states lately. But the unexpectedly competitive Kansas race has been a consistent bright spot — even though the party technically isn’t fielding a candidate. On Wednesday, the party got more good news in the state, as a new USA Today / Suffolk University poll showed Kansas Senator Pat Roberts (R) is trailing independent Greg Orman by five points, with the incumbent winning only 41 percent of the vote.

Enten makes the case that this “was actually a bad result for Orman”:

Twice previously, Public Policy Polling (PPP) found Orman up by 10 percentage points in a two-way matchup with Roberts. Fox News had Orman ahead by 6 points. Moreover, Suffolk has traditionally had a Democratic-leaning house effect, a measure of how a pollster’s results compare to other polls. The model adjusts for this, nudging Suffolk’s result 2 percentage point toward the GOP. Fox News surveys have a 3 percentage-point pro-Republican house effect, and PPP has a negligible one.

Aaron Blake wonders whether Orman’s lead can hold up:

The poll shows Orman’s favorable rating at 39 percent and his unfavorable rating at 25 percent. Those are good numbers — if they hold when more voters get to know him. Even among Republicans, Orman’s favorable/unfavorable split is a pretty-close 29/34. But lots of people still have yet to be introduced to Greg Orman, and it’s quite simply very hard to emerge from a hard-fought campaign with positive numbers like that. How does his positive image hold up after he’s carpet-bombed with ads labeling him a liberal (with little backup)?

Margaret Carlson comments on the Kansas Senate and governor races:

If [Kansas governor Sam] Brownback loses, his grand experiment dies with him, and his misadventure will give pause to other Republican governors who want to push through a right-wing agenda, even in conservative states.

As for Roberts, if he loses a fourth term to an independent, it shows that overly comfortable incumbents can be taken down by challengers other than Tea Party populists. President Barack Obama’s ability to enjoy two more years with Democrats in control of the Senate may come down to the victory of a candidate no one had heard of six weeks ago in a state where no one expected an upset.

Sargent thinks it’s no “exaggeration to say that three of the most important state-level experiments in conservative reform — all of which were outgrowths of the 2010 Republican triumph fueled by the Tea Party insurgency of Obama’s first term — are all, to varying degrees, standing in judgment before voters”:

Whoever wins in Wisconsin, Kansas, and North Carolina, it would probably be a mistake to read too much into what it says about public opinion and conservatism, since political races turn on so many factors. Indeed we may end up with something of a split verdict. But it’s striking that this cycle is shaping up as something of a test not just of the policies of the national party in possession of the White House, but of conservative governance as well.

John Cloud traveled to Alaska to cover another pivotal race:

Alaska is a notoriously difficult place to poll, but everyone assumes the contest is a dead heat. What has so far been a gentlemanly race between a good man who lost his dad here and a warrior who followed his wife here is about to change, for the meaner—a function of the stakes and the money that’s gushing in. Not just Rove’s millions, but Harry Reid’s, too. The moment Begich and I emerged from his SUV, a man paid to follow his every move with a camera asked why Begich opposed more oil-drilling jobs for Alaskans. (A strange question, since Begich has voted for more drilling and promises to vote for more.) Once we were out of camera range, Begich turned to me and smiled. He looked, for a moment, like a politician. “They will try anything,” he said. “But I know the state I grew up in. They don’t have that.”

Despite that, Republicans may be gaining ground in Alaska:

A survey shared with The Hill by Republican pollster Marc Hellenthal conducted for a coalition focused on ballot amendments found Sullivan with a lead over Begich, 46 percent to 42 percent. Dittman Research, a Republican firm that has a strong track record in the state, found Sullivan leading Begich 49 percent to 43 percent in a poll conducted for the pro-Sullivan U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Two recent automated polls also found Sullivan with a lead, though a pair of Democratic polls released in mid-September had Begich up by 5 points.

Last week, Sean Trende theorized that undecided voters may break towards Republicans:

The Democrats’ problem is that they seemingly find themselves in a position similar to that of Republicans in 2006: They are in tight races. But so far, they seem unable to move past where the fundamentals suggest they should be able to go: Recall again that their maximum showing has generally been bounded at 47 percent. … [S]ooner or later the undecided voters will begin to decide. And given that the Democrats are winning the votes of almost everyone who approves of the president’s job, they will have an uphill — though hardly insurmountable — battle with undecided voters.

If this theory is right, we should expect to see these races continue on the basic trajectory we’ve seen over the past few weeks: Democrats holding at their current levels. Eventually, Republicans should begin or continue to improve, as undecided voters engage and make up their minds, and as Republicans narrow the spending battles. Even if this theory is true, it won’t occur in every race, but it will be the general tendency.

Rove, as is his habit, talks up the GOP’s chances:

In the Real Clear Politics average of public polls, there has been a clear movement since Sept. 22 toward the GOP. Despite a significant recent increase in negative attack ads from Sen. Reid’s Super PAC and liberal and labor special-interest groups, 10 of the 11 Republicans in the most competitive races for Democratic Senate seats improved or maintained their ballot position. Republicans now lead in contests for eight Democratic seats, enough for a GOP majority