Ali Murat Yel defends Turkey’s reluctance to join the war coalition against ISIS:

Public opinion in Turkey holds that a Muslim cannot be a terrorist and any terrorist cannot be a Muslim. In other words, terrorism and Islam cannot be reconciled. This public conviction is certainly the real attitude of the President Recep Tayyip Erdogan who has formed the Alliance of Civilizations with Spain against the expectation in some quarters of a “clash of civilizations” and has been trying to restore peace with different ethnic groups in Turkey. The President himself and the majority of Turkish people believe that terrorism could be defeated intellectually not through waging war on them.

Turkish foreign policy has been formed on the principle of “zero problems with neighbors” because we believe that stability in the region would only bring more peace and wealth. … Instead of an external military operation the local politicians and people should come together and find their own solution according to their own realities and circumstances. Outsiders cannot understand all the local realities like the ethnic origins, sectarian divisions, or the political or ideological power structures of these peoples. Turkey, finally, does not want to be in the position of going to war in another, neighboring Muslim country.

Sanity! But we, thousands of miles away, know better. Amos Harel takes a look at the background role Israel is playing:

Despite the growing concern, it should not come as a surprise that the Netanyahu government has not yet taken any immediate steps against IS. The government has only announced that the organization would be considered illegal in Israel and the Palestinian territories, and decided to focus intelligence-gathering on the group’s activities in Syria and Lebanon. But while IS might not present an imminent threat at home, Netanyahu has been extremely eager to aid the Arab world in the battle against the group. Last week, the prime minister confirmed media reports that Israel was supplying intelligence to the new anti-IS international coalition. Jerusalem no doubt has useful information to contribute: For decades, it focused on acquiring first-rate intelligence about events in Syria, which it considered its toughest enemy.

Michael Crowley turns to Saudi Arabia, the linchpin of the coalition, and what King Abdullah al-Saud brings to the table:

While Saudi money has long helped nurture a fundamentalist Sunni doctrine that inspires groups from al Qaeda to Boko Haram, Islamic radicalism has come to threaten the king as well. … ISIS seems to have raised the king’s anxiety another notch, however. He has banned Saudis from traveling to join the fight in Syria, lest they return to threaten his regime. Last month Saudi authorities arrested dozens of suspects linked to ISIS — including members of an alleged cell plotting attacks within the country. But Abdullah wields a potent weapon in his defense: his influence over Saudi Arabia’s religious leaders. The king has a symbiotic relationship with his kingdom’s hardline clerics, whose words hold sway far across the Muslim world.

But Simon Henderson suspects that the Saudis will prefer to play both sides:

Despite the diplomacy of recent days, which suggests an emerging coalition that includes Saudi Arabia and will take on the fighters of the Islamic State in Iraq and perhaps Syria, the House of Saud will likely continue to try to balance the threat of the head-chopping jihadists, while also trying to deliver a strategic setback to Iran by overthrowing the regime in Damascus. From a Saudi point of view, the move of IS forces into Iraq contributed to the removal of Nouri al-Maliki in Baghdad, whom they regarded as a stooge of Tehran. Despite official support by Riyadh for the new Baghdad government, many Saudis who despise Shiites probably regard IS as doing God’s work.

Which is why this really is whack-a-mole. The administration, meanwhile, is engaging in linguistic contortions to explain how we’re not “coordinating” with Iran or Syria even if we’re talking to them and perhaps sharing intelligence:

“Coordinating means we talk directly to [the] Syrian Air Force and coordinate our attacks against ISIS with their operations against ISIS,” Christopher Harmer, an analyst with the Institute for the Study of War, told Foreign Policy, using one of the Islamic State’s acronyms. “That’s not happening, won’t happen.” But “deconflicting,” Harmer explained, means that the United States will monitor where the Syrian aircraft are flying and stay out of their way, thus avoiding any potential skirmishes. “That way we don’t accidentally intrude on their operations, or they on ours,” he said.

Harmer said the United States and Iran followed this protocol during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. “The U.S. did not coordinate with Iran, but Iran definitely deconflicted their normal military operations to avoid any unwanted interaction with the U.S., particularly in the Persian Gulf,” he said. In that case, Harmer said, the Iranian Navy held back patrol boats that had often harassed U.S. Navy ships in the Strait of Hormuz. “They backed way down off of their normal operations in order to deconflict with the U.S. operations,” Harmer said.

But Jacob Siegel rightly worries that Iran could become our shadow enemy in Syria:

As Iran showed in the last war in Iraq, when it armed and backed insurgent groups fighting U.S. forces, having a common enemy, as Saddam Hussein once was, won’t prevent Tehran from trying to counter American influence in the Middle East. For Iran, the question is what comes after ISIS. In Iraq there is already a Shia-led government in Baghdad broadly aligned with Tehran. But in Syria, where Shia are a minority, a post-ISIS future threatens to freeze Iran out.

To defeat ISIS, the U.S. is relying heavily on Sunni coalition partners to give its aims local legitimacy and ensure that constructing the post-ISIS political order won’t fall solely to America. Fearing the loss of its power, Iran could try to destabilize U.S.-led efforts in Syria, causing a protracted conflict that would weaken the allied participants. Alternately, if Tehran resigns itself to Assad’s ouster, it may seek other means to maintain its influence in Syria. One option would be controlling the political transfer of power from Assad, to ensure that the new government installed in Damascus remains receptive to Iranian interests. Then there’s the real long shot: that Iran reaches a détente with its Sunni rivals and accepts a power-sharing arrangement rather than a client state in Syria.

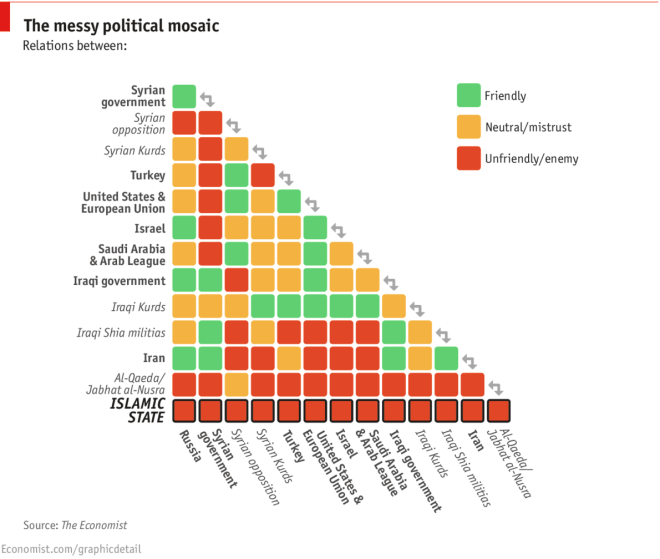

(Chart of Middle Eastern relationships via The Economist)