Douthat considers Obama’s case for war in Syria specifically and finds it lacking:

Writing in support of our initial northern Iraqi intervention, I argued that it passed tests that other Middle Eastern interventions, real and hypothetical, did not: There was a strong moral case for war and a clear near-term military objective and a tested ally to support and a plausible strategic vision (maintaining Kurdistan as a viable, American-friendly enclave, while possibly giving the government in Baghdad an incentive to get its act together) for what such an intervention could accomplish.

Based on what we’ve heard from the president, an expansion of the war to Syria does not pass enough of those tests to seem obviously wise or necessary or likely to succeed. We have no Kurd-like military partner in that country and we’re relying on Saudi training(!) to basically invent one, there isn’t even the semblance of a legitimate central government, and the actor most likely to profit from U.S. airstrikes is an Iranian-aligned dictator who makes Maliki look like Cincinnatus.

Josh Rogin sympathizes with the Free Syrian Army, whose leaders say that if the US provides them with arms, they will use them to fight Assad as well as ISIS:

[T]he Syrian opposition and the Free Syrian Army aren’t waiting for legal authorization to fight the Damascus regime; they are getting bombarded by Assad’s Syrian Arab Army every day, as it continues to commit mass murder of Syrian civilians through the siege of major cities, the dropping of barrel bombs, and the continued use of chlorine gas to kill innocents, according to international monitors. “The fight against ISIS is one part of a multi-front war in Syria. The brutal rule and poor governance of the Assad regime generated the conditions for ISIS become the global threat that it is today,” Syrian National Coalition President Hadi AlBahra told The Daily Beast on Thursday.

But Allahpundit thinks its crazy to expect the FSA to prevail, even with American backing:

Some dissenting U.S. analysts think there are moderates still in Syria we can work with but good luck picking them out of the gigantic crowd of Sunnis currently fighting Assad. For the sake of my own sanity, I need to assume that this whole “training the moderates” thing is just a big ruse being cooked up by the Pentagon as a pretext for inserting more reliable Sunni forces into the fray in Syria against ISIS. The Saudis have already offered to host the “training”; presumably, a whole bunch of the “Syrians” who end up being sent back onto the battlefield are going to be Saudi, Iraqi, and Jordanian regulars with U.S. special forces support. They could hit ISIS where it lives while posing as locals so as to spare their governments the political headache involved in sending their troops into the Syrian maelstrom. (They’d also suddenly be well positioned to threaten their other enemy, Assad.) If I’m wrong about that and we really are depending upon Syrian non-jihadis to somehow overrun ISIS in the east, hoo boy.

Jessica Schulberg points out that Washington has already been arming the Syrian rebels for a year, albeit covertly:

Obama’s decision to shift the Syrian training operation from the CIA to the Defense Department could also indicate that he sees a longer-term role for U.S. advisers in Syria than he did previously. The CIA’s advantage is that it is capable of carrying out small operations quickly, unencumbered by traditional bureaucratic restraints. The Defense Department, by contrast, requires authorization but is more capable of training a large, conventional fighting force. In this case, however, the $500 million Obama has requested from Congress for the Syrian opposition will likely prove inadequate. The U.S. has already spent over $2 billion in Syria, with little effect. It took more than $2 trillion of U.S. spending in Iraq to restore some semblance of a centralized government and military.

Juan Cole suspects that geopolitical considerations are at play here:

[I]n Iraq the outside great powers are on the same page. But in Syria, the Obama administration is setting up a future proxy war between itself and Russia once ISIL is defeated (if it can be), not so dissimilar from the Reagan proxy war in Afghanistan, which helped created al-Qaeda and led indirectly to the 9/11 attacks on the US. Obama had earlier argued against arming Syrian factions. My guess is that Saudi Arabia and other US allies in the region made tangible backing for the Free Syrian Army on Obama’s part a quid pro quo for joining in the fight against ISIL.

(Photo: A Syrian woman makes her way through debris following a air strike by government forces in the northern city of Aleppo on July 15, 2014. By Karam Al-Masri/AFP/Getty Images.)

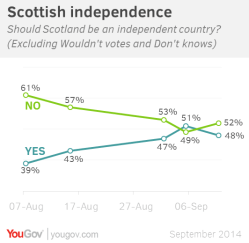

YouGov’s latest survey has No, on 52%, narrowly ahead of Yes, 48%, after excluding don’t knows. This is the first time No has gained ground since early August. Three previous polls over the past month had recorded successive four point increases in backing for independence. In early August Yes support stood at 39%; by last weekend it had climbed to 51%. …

YouGov’s latest survey has No, on 52%, narrowly ahead of Yes, 48%, after excluding don’t knows. This is the first time No has gained ground since early August. Three previous polls over the past month had recorded successive four point increases in backing for independence. In early August Yes support stood at 39%; by last weekend it had climbed to 51%. …