by Elizabeth Nolan Brown

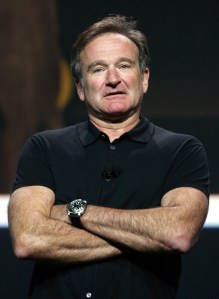

Yesterday Robin Williams died, seemingly from suicide. Scrolling through Facebook a few hours after the news broke, I found myself in a sea of RIP and this is so sad! and other, lengthier expressions of mourning for the beloved actor. One update stood out, from a friend of a friend. After acknowledging that it may sound cold, she wrote:

I just want to put it out there that it is also ok not to have any feelings when something bad happens to a celebrity.

This was met with initial, emphatic approval from a few, quickly followed by admonitions. Didn’t she get the memo that we were all supposed to be using this as a PSA about mental health? They bet she wouldn’t be singing this tune if she or someone she knew had suffered from depression!

Now there’s nothing wrong with using the surprising (apparent) suicide of a surface-happy comedian as a catalyst for discussing mental health issues. But how absurd to suggest it’s wrong not to. Maybe some people would prefer to remember the man’s life and work rather than his demons. Maybe some people who are intimately aware of the toll depression can take (or the pain a loved one’s suicide can cause) are loathe to latch their very personal pain to online discussions of a stranger with strangers. Maybe not everybody has to react in the same emotional tones.

But then why say something at all? That was another criticism hurled at this Facebook poster. Why couldn’t she have just kept her big non-mourning mouth shut?

Permit me a brief digression. As a college theater major, I once auditioned for a play that would be directed by a visiting Nigerian professor, Esiaba Irobi. For this play, Professor Irobi decided to eschew traditional callbacks and instead gather us all together and watch while we engaged in various games and activities. Near the end of the audition, we were all invited in a circular procession around the room, repeating after Irobi as he sung out some sort of call-and-response funeral dirge.

We were explicitly told not to act—this wasn’t an exercise to see how well we could feign grief. The professor said he wanted to see how we moved. There were drums. And there were quickly tears, all around me. Not just soft, subtle tears dotting my classmates’ cheeks but big, loud, hearty sobs. It confused the hell out of me. We weren’t actually at a funeral. We didn’t even have a fictional backstory for this procession, nor could we understood a word Irobi sang. Sure, his voice could carry emotion well, but I felt skeptical that the crying crew, which made up about half the room of auditioners, weren’t putting on a bit of a show.

Later, I brought this up with my then-boyfriend, who had also been at the auditions. He assured me his grief and that of those he’d talked to had been genuine. Then he told me it was sad that I was so closed off from my emotions that I couldn’t experience what they had. He felt sorry for me.

Because I was young, it genuinely stung and worried me. I am far from an emotionally repressed person, nor a non-demonstrative one. I’ve been known to cry at country songs and Law & Order episodes. So why couldn’t I feel sad over this imaginary scenario that had so tugged at my classmates’ heartstrings? What was wrong with my emotional response?

Nothing, is obviously the answer. There is no correct way to grieve. There is no correct way to mourn those you love, or to mourn acquaintances, or to mourn celebrities and strangers. And trying to conjure an inauthentic emotional response will only make you feel worse. But even knowing this, I admit—when popular public figures die, there’s always a moment in which I feel just like I did in that audition. Why does everyone seem so much more upset than I am? Why am I not reacting the same way?

This is why I’m glad my Facebook friend didn’t keep her mouth shut. There is nothing wrong with feeling genuine sadness over the passing of an entertainer you enjoy and admire. There is nothing wrong with being stung by the way Williams seems to have went. There is nothing wrong with posting Mrs. Doubtfire stills to Instagram and heartfelt missives on your Twitter timeline in response, if the spirit moves you. And the “normalcy” of these responses is shown in the likes and retweets and expressions of solidarity with which they’re met. Collective catharsis exerts a powerful pull.

But in the age of all this public emoting—some no doubt genuine, some signaling—it can be very easy to forget that not everyone is “deeply saddened” by the news of Williams’ death. Some aren’t even moderately saddened. And that’s okay, too.

Update: Readers responded to this post here. You can also view all the Dish’s coverage of Robin William’s death here.

(Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)