Wan Chai, Hong Kong, 8.30 am

Wan Chai, Hong Kong, 8.30 am

Readers expand the discussion on whether the Dish should just bump up its $19.99 subscription price to 20 bucks:

Apparently it's is also effective to drop the $ sign on prices.

Another reader:

According to at least one study on the penny (pdf), the true purpose of having prices end in .99 is not to "trick" consumers into believing that an item costs less than it really does. Rather, stores use these prices to deter theft by employees. If something is priced with an even amount, say $20, the consumer is likely to pay with exact change. It's fairly easy for a cashier to just pocket the $20 bill without ever ringing up the purchase. If an item is priced at $19.99, the cashier will probably have to make change. It'll be pretty obvious if she takes a penny out of her pocket, so she will have to enter the purchase into the register.

Thought this theory might be of interest to you. And, if true, it implies that it is pretty pointless to price something at $19.99 over the Internet.

Another:

Steven Landsburg offered this explanation of 99-cent pricing in his 1993 book, The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life:

The phenomenon of "99-cent pricing" seems to have first become common in the nineteenth century, shortly after the invention of the cash register. The cash register was a remarkable innovation; not only did it do simple arithmetic, it also kept a record of every sale. That’s important if you think your employees might be stealing from you. You can examine the tape at the end of the day and know how much money should be in the drawer.

There is one small problem with cash registers: They don’t actually record every sale; they record only those sales that are rung up. If a customer buys an item for $1 and hands the clerk a dollar bill, the clerk can neglect to record the sale, slip the bill in his pocket, and leave no one the wiser.

On the other hand, when a customer buys an item for 99 cents and hands the clerk a dollar bill, the clerk has to make change. This requires him to open the cash drawer, which he cannot do without ringing up the sale. Ninety-ninecent pricing forces clerks to ring up sales and keeps them honest." (http://books.google.com/books?id=qTBgMMxeJ5IC&pg=PA19)

It's a cute theory, but even Landsburg notes some holes. What about states with sales tax, where an item priced in whole dollars would still require change? And why has it persisted, even after the advent of scanners and electronic registers that record sales even when no change is required?

The question seems particularly troubling to economists, because a strong consumer preference for $19.99 over $20 would seem to wreak havoc with the notion of consumers as rational actors. Nevertheless, over the last twenty years, a growing number of empirical studies and experiments have confirmed that 99-cent pricing actually works.

One explanation is for that success is that 99-cent pricing signals to consumers that the item is a bargain, because it's most often used on bargain goods. Consumers aren't buying these items because they mistakenly think that missing penny makes them meaningfully cheaper, the theory suggests, but because they've been flagged as discounts.

A second is that consumers – or at least, some significant subset of consumers – process prices in two discrete units, before and after the decimal. Some people, perhaps don't find it worthwhile to invest the time and effort necessary to pay close attention to prices, and merchants calibrate their pricing to take advantage of their inattention.

You've actually been running your own experiment, with interesting results. There is, practically speaking, no real difference between those sums. At the moment, all contributions are voluntary – even the leaky paywall hasn't yet been put in place – and it's hard to believe that readers who will voluntarily hand over $19.99 would begrudge you the additional penny. And although subscribers are prompted with the $19.99 minimum, they have to manually enter the amount, and it's easier to just put down $20.

Indeed, that's exactly what nearly two thousand of them did. The only catch? Twice as many took the trouble to type out $19.99. I'd say that's fairly solid data in support of the theory that $20 just feels like more money – and that many readers are more likely to take the plunge and invest in the site if that threshold isn't crossed.

In a roundup of the most popular film and TV shooting locations, a cafe in LA stands out:

The Quality Cafe doesn't even function as a real diner anymore. It stopped serving meals in 2006, but it's been doing pretty well for itself as a film location over the past few decades … So now you know: If you ever get the feeling that all the diners used in Hollywood movies look the same, that's because they probably are.

Drum recently argued that it would be illegal to mint a trillion dollar platinum coin in order to avoid the debt ceiling. Lizardbreath at Unfogged, who is a lawyer in New York, counters:

I don’t think a court would stop it, and I’m sure that a court that did stop it would be acting unusually and for politically motivated reasons. Courts are expected to do what legislatures say, not what they mean: “legislative intent” can only be considered where there’s an ambiguity in the law. Even if what the legislature said is obviously not what they meant, courts are still expected to follow the letter of the statute. And the platinum coin statute isn’t ambiguous (unless there’s something in the wording I’m missing): the treasury can mint platinum coins, and they’re real money.

Regardless, Felix Salmon sees the platinum coin option is reckless:

[I]t would effectively mark the demise of the three-branch system of government, by allowing the executive branch to simply steamroller the rights and privileges of the legislative branch. Yes, the legislature is behaving like a bunch of utter morons if they think that driving the US government into default is a good idea. But it’s their right to behave like a bunch of utter morons. If the executive branch failed to respect that right, it would effectively be defying the exact same authority by which the president himself governs. The result would be a governance crisis which would make the last debt-ceiling fiasco look positively benign in comparison.

McArdle foresees other consequences:

I think–and I assume the White House does as well–that there's a substantial risk that this sort of nominally-legal-but-obviously-tendentious reading of the law would trigger a selloff in US bonds. Minting a $1 trillion coin neatly end-runs GOP obstructionists, but only by proving that the president himself has little respect for the institutional restraints on his office. So while the pundit in me is eager to see how this would play out, the US citizen in me is afraid of the effect that this would have on my country. I assume that our president shares these sort of concerns.

Cowen believes that exploiting the platinum coin loophole would be counterproductive:

[L]et’s say that — somehow — the whole thing miraculously worked out well from start to finish. The testier Republicans would in fact get exactly what they want. They would receive isolation from any negative consequences from brinksmanship, and a new narrative about how President Obama is a fascist incarnate.

Tomasky thinks the proposal doesn't pass the laugh test:

Can you imagine a president giving a prime-time, Oval Office address and saying, what we're gonna do, people, is mint a coin worth $1 trillion. That just doesn't pass any laugh test I can conceive of. I'd bet Obama would drop 12 points in the polls within five days of making such an announcement.

But Josh Barro isn't so quick to dismiss the idea:

[W]e need to compare the platinum coin option against others on the table. For example, we could hit the debt ceiling and the government could start leaving about 40 percent of its bills unpaid. The president could accede to Republican demands for near-term spending cuts (of an as-yet-unspecified nature) in addition to the amounts from the Budget Control Act sequesters, which would cause another recession. Or he could assert authority under the 14th Amendment to continue issuing debt, notwithstanding the debt ceiling, which would lead to court battles and probably impeachment. (The 14th Amendment play sounds less "silly" than the platinum coin, but it's actually on much shakier legal ground.) Minting the platinum coin would be less economically damaging than any of the above options, which is why Obama should announce he will pursue it if the debt ceiling is not raised.

Very important facts about the sloth to help put your life in perspective:

John Boehner claims that Republicans aren't afraid of the sequestration, which includes major defense cuts. Chait wonders whether the Speaker will lose his nerve:

Boehner is asserting that Republicans don’t actually care that much about cutting defense — that replacing the sequester is something Democrats want. Just because Boehner says this doesn’t make it true. He may be holding his defense hawks in line publicly, but the question is whether he can keep them in line as the negotiations proceed and the prospect of implementing the cuts grows more real.

I'd be fine with the sequester precisely because of its focus on defense. But it needs to be adjusted to be less crude – and the relevant government agencies need more flexibility in timing and arranging the cuts. What strikes me is that Boehner may be realizing that he does not have the popular support for cutting Medicare as he wants and that the sequester may be the only politically feasible way of doing it. Especially if Obama proposes major tax reform to come up with revenues to slow the cuts in Medicare.

Meep meep.

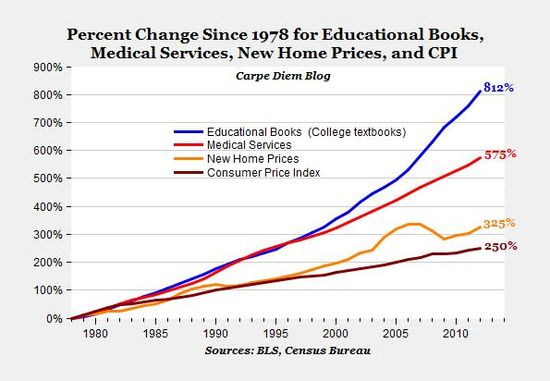

Mark Perry created the above chart:

The 812% increase in the price of college textbooks since 1978 makes the run-up in house prices and housing bubble (and subsequent crash) in the 2000s seem rather inconsequential, and the nine-fold increase in textbook prices also dwarfs the increase in the cost of medical services over the last three decades.

Jordan Weissmann puts the cost in perspective:

According to the National Association of College Stores, the average college student reports paying about $655 for textbooks and supplies annually, down a bit from $702 four years ago. The NACS credits that fall to its efforts to promote used books along with programs that let students rent rather than buy their texts. But to put that $655 in perspective, consider this: after aid, the average college student spends about $2,900 on their annual tuition, according to the College Board. We're not talking about just another drop in the bucket here.

Max Fisher highlights an air freshener being sold in Iran:

The Post’s Tehran correspondent, Jason Rezaian, sends on the above photo of the Khamenei air freshener, which is apple-scented, if you’re wondering. It’s just the thing to add some revolutionary aroma to your late-model Samand. The item was procured by a friend, Jason says, at the Tajrish bazaar in northern Tehran. It cost 10,000 Iranian rials, or about 81 cents. And no, sadly, he is not taking orders. But I’ve asked him to let me know if he comes across a cherry-scented Khomeini or "new car" Rafsanjani.

Update from an Iranian reader:

The cult of personality they are trying to build around Khamenei is reaching North Korean levels. Too bad for them the majority in Iran cant give a flying fuck about the monster. Back in the '80s, Khomeinei was a charismatic leader and had a real following, yet he wouldn't even allow his pic to be posted on the national currency – he didn't need it. He was popular among the more religious and traditional sectors of the society without any such propaganda. Khamanei is not, and that's why his gang tries so hard to turn him to a saint, to recreate that aura around the Ayatollah.

In examining Stephen Hawking's network of assistants, technicians and machines, Hélène Mialet notices the collective nature of his genius:

Traditionally, assistants execute what the head directs or has thought of beforehand. But Hawking’s assistants – human and machine – complete his thoughts through their work; they classify, attribute meaning, translate, perform. Hawking’s example thus helps us rethink the dichotomy between humans and machines.

It also helps us rethink the dichotomy between those who are in charge, and those who execute. While far less embodied, just think about Obama’s brain trust on the night of the election: Were they not part of Obama’s brain? They helped make his success happen; they were as, if not more, invested in the outcomes; and they looked just as exhausted as Obama’s mind probably felt.

Someone who is powerful is a collective, and the more collective s/he becomes, the more singular they seem.

Thanks for being out there, Dishheads.

A small Beltwayish sign that the neocons may be over:

And another reminder of something Barack Obama said when he was a candidate:

I don't want to just end the war. I want to end the mindset that got us into war in the first place.

In the first term, he did the first. In the second, "the change we can believe in?"