[Re-posted from earlier today]

The shift in my own mind has happened gradually. Even up to a year ago, I was still getting my New York Times every morning on paper, wrapped in blue plastic. Piles of them would sit in my blog-cave, read and half-read, skimmed, and noted.

Until a couple of years ago, I also read physical books on paper, and then shifted to cheaper, easier, lighter tablet versions. Then it became a hassle to get the physical NYT delivered in Provincetown so I tried a summer of reading it on a tablet. I now  read almost everything on my iPad. And as I ramble down the aisle of Amtrak’s Acela, I see so many reading from tablets or laptops, with the few newspapers and physical magazines seeming almost quaint, like some giant brick of a mobile phone from the 1980s. Almost no one under 30 is reading them. One day, we’ll see movies with people reading magazines and newspapers on paper and chuckle. Part of me has come to see physical magazines and newspapers as, at this point, absurd. They are like Wile E Coyote suspended three feet over a cliff for a few seconds. They’re still there; but there’s nothing underneath; and the plunge is vast and steep.

read almost everything on my iPad. And as I ramble down the aisle of Amtrak’s Acela, I see so many reading from tablets or laptops, with the few newspapers and physical magazines seeming almost quaint, like some giant brick of a mobile phone from the 1980s. Almost no one under 30 is reading them. One day, we’ll see movies with people reading magazines and newspapers on paper and chuckle. Part of me has come to see physical magazines and newspapers as, at this point, absurd. They are like Wile E Coyote suspended three feet over a cliff for a few seconds. They’re still there; but there’s nothing underneath; and the plunge is vast and steep.

Which is why, when asked my opinion at Newsweek about print and digital, I urged taking the plunge as quickly as possible. Look: I chose digital over print 12 years ago, when I shifted my writing gradually online, with this blog and now blogazine. Of course a weekly newsmagazine on paper seems nuts to me. But it takes guts to actually make the change. An individual can, overnight. An institution is far more cumbersome. Which is why, I believe, institutional brands will still be at a disadvantage online compared with personal ones. There’s a reason why Drudge Report and the Huffington Post are named after human beings. It’s because when we read online, we migrate to read people, not institutions. Social media has only accelerated this development, as everyone with a Facebook page now has a mini-blog, and articles or posts or memes are sent by email or through social networks or Twitter.

And as magazine stands disappear as relentlessly as bookstores, I also began to wonder what a magazine really is. Can it even exist online? It’s a form that’s only really been around for three centuries – and it was based on a group of people associating with each other under a single editor and bound together with paper and staples. At The New Republic in the 1990s, I knew intuitively that most people read TRB, the Diarist and the Notebook before they dug into a 12,000 word review of a book on medieval Jewish mysticism. But they were all in it together. You couldn’t just buy Kinsley’s perky column. It came physically attached to Leon Wieseltier’s sun-blocking ego.

But since every page on the web is now as accessible as every other page, how do you connect writers together with paper and staples, instead of having readers pick individual writers or pieces and ignore the rest? And the connection between writers and photographers and editors is what a magazine is. It defines it – and yet that connection is now close to gone. Around 70 percent of Dish readers have this page bookmarked and come to us directly. (If you read us all the time and haven’t, please do). You can’t sell bundles anymore; and online, it’s hard to sell anything intangible, i.e. words, because the supply is infinite. You no longer control the gate through which readers have to pass and advertizers get to sponsor. No gateway, no magazine, no revenue – and massive costs in print, paper and mailing.

I know a bit about these things, having edited a weekly magazine on paper for five years and running this always-on blogazine for twelve. It’s a different universe now. And to me, the Beast’s decision to put Newsweek Global on a tablet and kill the print edition is absolutely the right one. To do it now also makes sense. To have done it two years ago would have been even better. Why wait?

[I]f print is a money-loser — and I keep hearing that is is, for newspaper after newspaper — why not end it now, today, and go purely digital? Why shouldn’t newspapers around the world, or at least in the most internet-saturated parts of the world, just stop the presses — especially if they know they’ll have to do it anyway, and in the meantime the cash is draining away? What are the restraining factors? Habit and tradition? Powerful executives who have known the print world for so long that they can’t imagine life without it? The half-conscious feeling that paper and ink are real in ways that pixels and bits are not, and that if you only have pixels and bits you might as well be just a blogger, without a saleable product you can hold in your hand? This inquiring mind really, really wants to know.

That’s Alan Jacobs with whom I heartily agree. The reason is that these huge corporations, massive newsrooms, and deeply ingrained advertizing strategies become interests in themselves. No institution wants to dissolve itself. Getting that old mindset to accept that everything that it has done as a business and editorial model is now over, pffft, gone, is very, very hard. But they often cannot adjust because they are too big to move so quickly and because new sources of information and new flows of information keep evolving, and because no one really wants change if it means more job insecurity. We’re human. It’s not pleasant realizing that the entire business and editorial model for your entire career is kaput.

But that doesn’t mean the end of journalism, just of the physical objects that convey journalism. The “media” is simply Latin for the way in which information is transmitted. It’s the way one idea or fact or non-fact goes from someone’s brain into another’s. Today journalism is consumed by people at work, like you, reading to stave off boredom, or following an election, or because they love a particular site, or just find it productive, ahem, to check out the latest meme or cool video or righteous rant online. Then we watch TV, but not the nightly news, apart from the older generations. The generations below mine get their news online all day long and through Stewart/Colbert. The other way of reading is leaning back, enjoying long-form journalism or non-fiction in book or essay form – at the weekend or in the evenings or on a plane. And the tablet is so obviously a more varied, portable, simple vehicle to deliver a group of writers tied together in one actual place, which cannot be disaggregated, than paper, print and staples. And far less expensive. Print magazines today are basically horses and carriages, a decade after the car had gone into mass production. Why the fuck do they exist at all, except as lingering objects of nostalgia?

So this is a radical change and will be wrenching in transition, but is actually essential to saving the journalism we still need:

It is important that we underscore what this digital transition means and, as importantly, what it does not. We are transitioning Newsweek, not saying goodbye to it. We remain committed to Newsweek and to the journalism that it represents. This decision is not about the quality of the brand or the journalism—that is as powerful as ever. It is about the challenging economics of print publishing and distribution.

“Challenging” is a euphemism for impossible. Maybe a couple of magazines will survive in print as status symbols at the high end, or as supermarket check-out tabloids at the lower stratosphere. But I doubt even that. Tablet subscriptions seem to me the only viable way forward. The good news is that the savings from this can be plowed back into journalism if revenues from subs and ads revive. In the end, the individual who will decide if magazines survive at all, even on tablets, will be readers, and their willingness to pay for writing in that form, when they go online and get it for free. Yep, it’s up to you. And all your invisible hands.

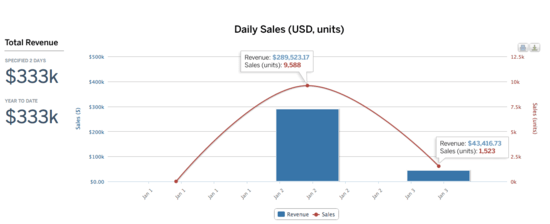

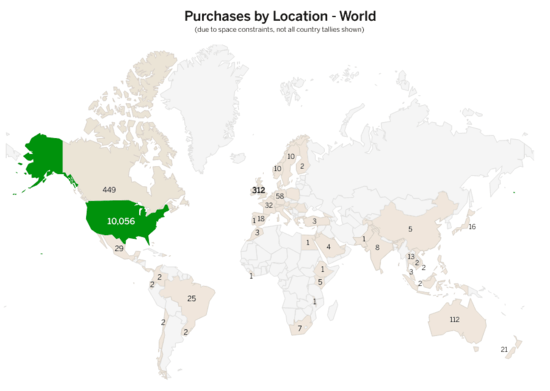

After some urgent soul-searching, we’ve decided that this is your blog and that you deserve to see as much behind the curtain as possible, without disclosing individual employees’ private information. We just have to trust that the data won’t hurt the site, whatever side of the line we fall. So, as soon as we gather up all the data, we’ll give you our rough calculation of our estimated budget for our first year and data on how much progress we have made so far. Felix isn’t far off with $750,000 – but we were a little more conservative in guessing future unknown technological costs, and so we calculated a slightly higher number, and a steeper hill to climb. I’m a fiscal conservative, remember.

After some urgent soul-searching, we’ve decided that this is your blog and that you deserve to see as much behind the curtain as possible, without disclosing individual employees’ private information. We just have to trust that the data won’t hurt the site, whatever side of the line we fall. So, as soon as we gather up all the data, we’ll give you our rough calculation of our estimated budget for our first year and data on how much progress we have made so far. Felix isn’t far off with $750,000 – but we were a little more conservative in guessing future unknown technological costs, and so we calculated a slightly higher number, and a steeper hill to climb. I’m a fiscal conservative, remember.  read almost everything on my iPad. And as I ramble down the aisle of Amtrak’s Acela, I see so many reading from tablets or laptops, with the few newspapers and physical magazines seeming almost quaint, like some giant brick of a mobile phone from the 1980s. Almost no one under 30 is reading them. One day, we’ll see movies with people reading magazines and newspapers on paper and chuckle. Part of me has come to see physical magazines and newspapers as, at this point, absurd. They are like Wile E Coyote suspended three feet over a cliff for a few seconds. They’re still there; but there’s nothing underneath; and the plunge is vast and steep.

read almost everything on my iPad. And as I ramble down the aisle of Amtrak’s Acela, I see so many reading from tablets or laptops, with the few newspapers and physical magazines seeming almost quaint, like some giant brick of a mobile phone from the 1980s. Almost no one under 30 is reading them. One day, we’ll see movies with people reading magazines and newspapers on paper and chuckle. Part of me has come to see physical magazines and newspapers as, at this point, absurd. They are like Wile E Coyote suspended three feet over a cliff for a few seconds. They’re still there; but there’s nothing underneath; and the plunge is vast and steep. the

the